Both sides are losing Trump's war on universities (Part 1)

A new series on the follies of the Trump administration's ongoing battle with universities and how both sides can do better. Part 1 discusses universities' value to society and their problems.

Imagine American universities as a cancer patient. On the one hand, their doctors—the Trump administration—are proposing treatments that disproportionately attack their healthy cells. On the other hand, the patient—academia—is insisting that the proposed treatments are harmful because they don’t really have cancer.

At universities across the country, the Trump administration sees out-of-control antisemitism, illegal discrimination, and disciplines—disproportionately in the social sciences and humanities—becoming politically radicalized monocultures; subordinating their academic standards, professional responsibilities, and their peers’ academic freedoms to radical politics; and teaching their students to hate America and the west. The administration sees these problems as interconnected.

But their solution, so far, has largely been to: make drastic cuts to the hard sciences; haphazardly target international students in ways that will make fewer of the world’s best and brightest minds want to study here; aggressively prosecute civil rights violations only at a small handful of elite schools, often skirting due process and thereby making their prosecutions (which have some merit) vulnerable in the courts, while leaving the rest of the academy largely unscrutinized; and undermine academic and expressive freedoms in ways that cede any moral high ground they might otherwise have had on those issues.

In response, university administrators are waxing poetic about all of the public goods universities provide, but (with few exceptions) they aren’t acknowledging nor taking meaningful steps to address the scale and severity of the very real problems on campus. These problems have caused measurable declines in public trust, enrollments (especially among men), and job prospects for graduates over the past decade, which universities can’t afford to ignore forever, regardless of what happens over the next four years.

Among the minority of professors and professional organizations (like Heterodox Academy) that do publicly acknowledge the problems on campus, we (rightly) criticize the Trump administration’s approach as going too far in many areas, but then we rarely offer any concrete and workable alternatives. We talk in vague terms about how we can reform universities internally, without addressing the obvious question of “why hasn’t that happened already?”. And some of us acknowledge the need for governments to play a role in righting the ship, but we rarely suggest specific alternatives to the Trump approach.

So, neither side is helping their cause, but it’s not too late to right the ship. In fact, I think it’s possible for universities and the Trump administration to reach something like a ‘grand bargain’ that would satisfy most people in both camps, outside of the most extreme elements, as well most of the American public.

This is the first post of a three-part series on how I think this could be done. In Part 1 (today’s post), to set the scene, I will summarize some of the evidence that universities have both enormous value to society and enormous problems that all but the most committed far-left radicals should want to fix.

In Part 2, I will take a closer look at the specifics of the Trump administration’s and universities’ approaches to the current conflict—offering critiques and what I think are constructive suggestions that are in the spirit of both institutions’ goals and best interests.

In Part 3, I will outline my idea for a grand bargain and how it might be reached.

As always, I welcome and look forward to any comments and critiques.

Universities have big value and big problems.

These two things can be true at the same time, as I outline below using illustrative points. My points are surely not exhaustive—that would be a book-length project at least—and others have already written books about several of these points. But, I think it’s important to start my series here, because there still seem to be too many people in the Trump administration who don’t fully grasp universities’ value, and too many in universities who don’t fully grasp our problems. We can’t have a constructive dialogue unless both sides of the argument see both sides of the issue.

Universities’ value

Publicly funded university research plays a critical role in U.S. economic dominance. For example, a recent paper (updated version here) from the Dallas Federal Reserve estimates that U.S. government-funded non-defense research and development (R&D) brings 140-210% returns on investment to the economy, pays for itself fiscally (because its contributions to growth increase tax revenue), and was responsible for 20% of business-sector productivity since World-War II. (Here is a good explainer of the study.) The authors conclude that scientific research is substantially under-funded compared to what would be in the country’s best interest. Non-defense R&D accounted for roughly 1.5% of 2024 federal spending (~0.4% of GDP). The federal deficit is currently ~6% of GDP. All of this implies that cutting non-defense R&D spending is a terrible way to address the federal government’s (very real) deficit problem. Concentrating these cuts in medical sciences is likely to be very bad for our health.

Publicly funded U.S. university research has produced breakthroughs that have literally saved billions of lives. Think: enhanced crop varieties that led to the Green Revolution (credited with saving over a billion lives alone); antiretroviral treatments for HIV/AIDS; vaccines for polio and countless other diseases; mRNA technologies that produced the COVID-19 vaccines; cancer treatments that have dramatically increased survival rates, especially in children; literally every single new drug approved by the FDA for medicinal purposes between 2010 and 2016 (and probably other years too). Of course, there have been countless other transformative U.S. publicly funded breakthroughs beyond this lifesaving list, such as the Internet, microchips, GPS, lithium-ion batteries, hydraulic fracturing (fracking) and horizontal drilling, weather forecasting, and more.

The private sector cannot replace these benefits at scale if universities’ government funding were drastically cut. There are three reasons for this.

First and foremost, universities’ largest benefits are public goods. Econ 101 tells us that the private sector does not have the incentive to provide public goods at the scales most beneficial to society. This is the same reason we need governments to build and maintain our roads, bridges, and parks. In fact, because university research and education are public goods, they increase private-sector productivity and investment rather than crowding it out (see the links above).

Second, universities and some of their most impactful research enterprises (e.g., in medicine or engineering) have enormous start-up capital costs that most private actors cannot comparatively scale. For example, the new private University of Austin just welcomed its first 92-student cohort this past academic year, after raising hundreds of millions of dollars in seed capital. That’s a great model for them (and other small private schools that don’t take government funds, like Hillsdale College), but it can’t scale up to replace current universities—especially in capital-intensive STEM fields (which these colleges both lack)—without government funds.

Third and relatedly, even if it were possible for the private sector to replace universities’ essential functions (which it’s not), it would take years to decades to build the replacements up, due to their high brick-and-mortar start-up costs. So, even in the best-case scenario, cutting today and hoping the private sector fills the gap would result in a lost decade or more of American education and innovation in between.

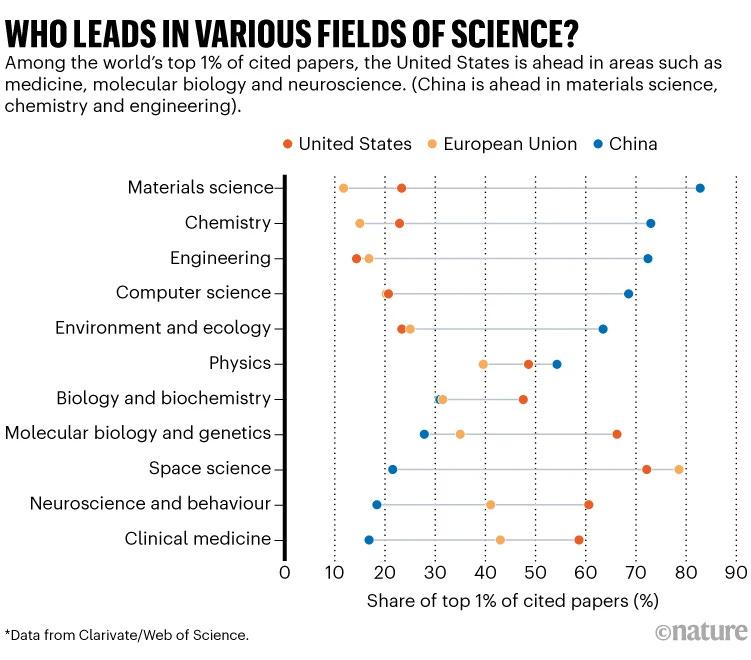

Balances of 21st-century geopolitical power will likely be won and lost on artificial intelligence (AI) and other high-tech sectors. Maintaining U.S. dominance in research and talent pipelines therefore seems important. China is catching up to us in research output, and they are already ahead in physical science research, by some measures. (See below.) But U.S. universities are still the envy of the world—dominating world university rankings, for example. Let’s keep it that way, and let’s catch up in the areas where we’re falling behind.

A university education is (still) associated with higher earnings, better health, and higher life satisfaction. This means that, even if universities have lost their way recently in some areas, we should want to help them re-focus and expand on the core value propositions for students, not tear them down.

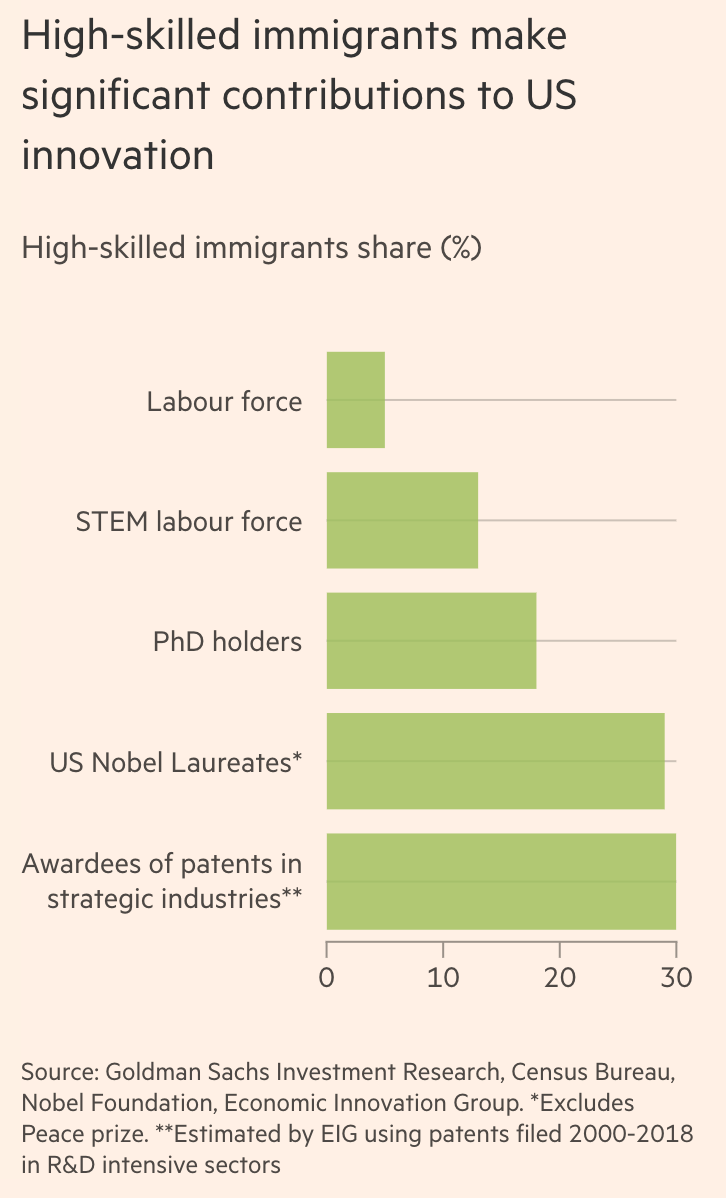

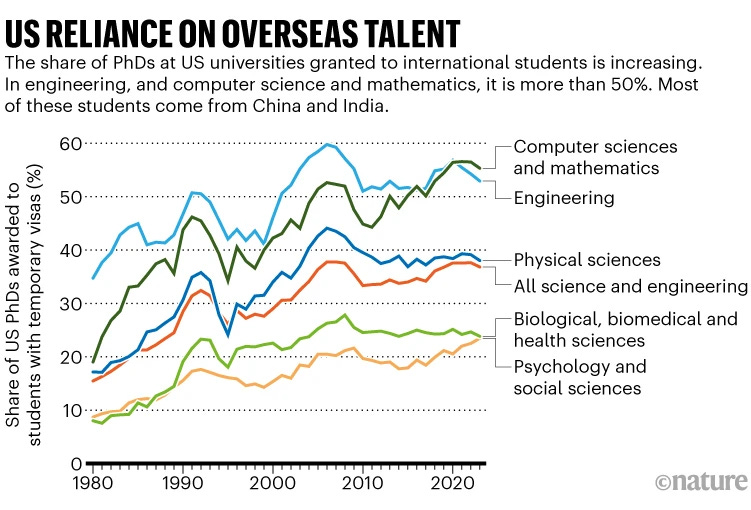

International students and scholars have been critical to U.S. dominance in science, research, the knowledge economy, and the economic benefits of these. The U.S. does not have the world’s biggest population, nor the world’s best K-12 education system, especially in STEM. Instead, our superpower in the knowledge economy is that we attract the best and the brightest from all over the world to come study here, and many of these people stay and build businesses or research and teach in our universities. One third of U.S. Nobel Laureates (see below) and 55% of U.S. billion-dollar start-up founders are immigrants, for example. International students also provide the U.S. with immeasurable soft power. People may decry or mock Harvard for enrolling the sons and daughters of foreign leaders, but what a great opportunity to export American ideas and grow American networks of influence. Having a bunch of world leaders with fond experiences of—and friends in—America is undoubtedly good for America.

All things considered, universities—and the international students they attract—are essential aspects of American greatness. If the federal government wants to make America great (again), they should want to fix universities and build them up, instead of tearing them down.

Universities’ problems

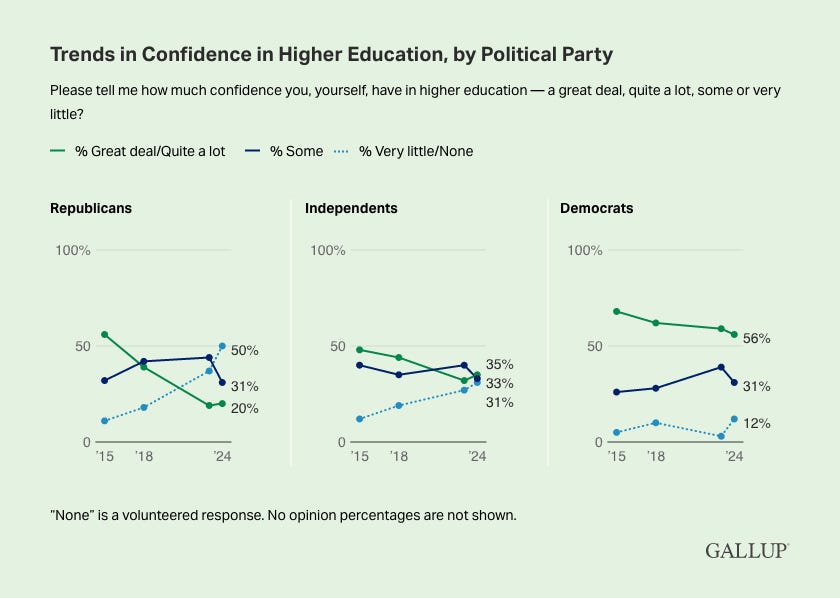

Universities have alienated more than half of the country. For example, one third or fewer of Republicans and Independents told Gallup in 2024 that they had “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in higher education. The fraction of Democrats with high confidence in higher education was barely more than half (see below). “Political agendas”—including “Indoctrination/Brainwashing/Propaganda”, “Too liberal/political”, “Not allowing students to think for themselves/Pushing their own agenda”, “Too much concentration on diversity, equity and inclusion”, and “Too socialist”—were the most common reason respondents gave for lack of trust. This explains why universities’ trust problems began abruptly around 2015, when their politics shifted sharply in these directions (see below). Many other polls have found similar patterns.

Universities routinely make a mockery of federal laws. For at least the past decade—and especially over the past five years—universities have pervasively, and often explicitly, made hiring, promotion, and other decisions about educational and employment benefits (or punishments) on the basis of race and gender, in violation of Titles VI, VII, and IX of the Civil Rights Act. Many have also violated the First Amendment (public universities) or contracts law (private universities) by ignoring or selectively enforcing their free expression policies. I have written about this before, so I won’t belabor this point. But the evidence is overwhelming. John Sailer and Chris Rufo of the Manhattan Institute, and Aaron Sibarium of the Washington Free Beacon, for example, have published slam-dunk evidence of illegal discrimination at dozens of universities. In many of the cases I know, the university leaders participated in these illegal activities because they felt immense social and even career pressure from their colleagues to do so. If that doesn’t signal a need for serious institutional reform—including government oversight—I’m not sure what would.

Several academic disciplines have been so corrupted by radical politics that their professional associations are publicly explicit about this. Consider, for example, the American Sociological Association, whose website proudly features a list of their dozens of political statements, all of a narrow persuasion, and whose annual conference themes over the past decade have almost exclusively been ‘social-justice’ (as defined by critical theories) related, including “Intersectional Solidarities: Building Communities of Hope, Justice, and Joy” (2024), “Emancipatory Sociology” (2021), “Power, Inequality and Resistance at Work” (2020), “Engaging Social Justice for a Better World” (2019), “Feeling Race: An Invitation to Explore Racialized Emotions” (2018), “The Culture, Inequalities, and Social Inclusion Across the Globe” (2017), and “Rethinking Social Movements: Can Changing the Conversation Change the World?” (2016). These political commitments are not just performative; they also make it difficult to interrogate important scholarly questions in the field and train students to the highest standards of rigor. Sociology is far from unique here. Similar charges have been made against Anthropology, classics, American Studies (which might be better-described as “anti-American studies”, former Harvard President Larry Summers once remarked) and other “area studies”, education, social work, and psychotherapy, to name a few.

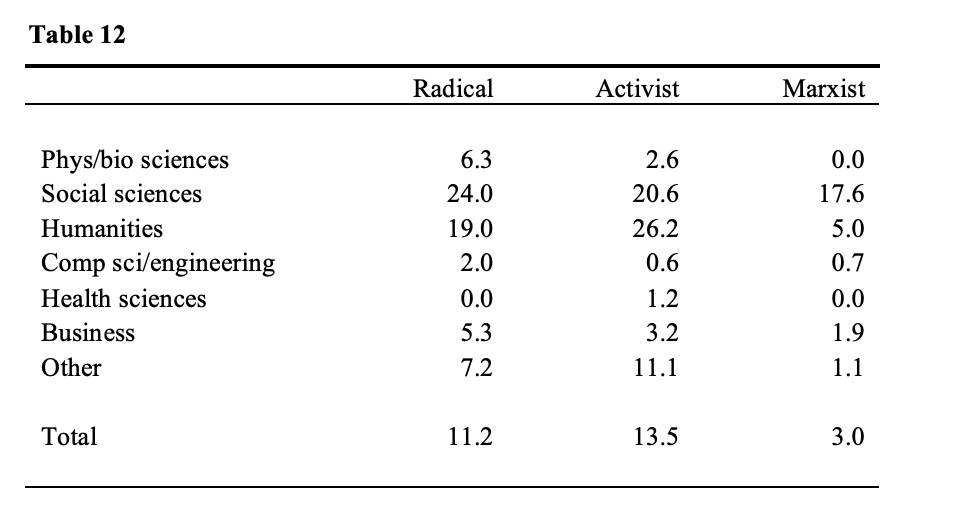

The graphs below report fractions of professors self-identifying as “radical”, “activist”, “Marxist”, or “socialist” in surveys from 2006 (top) and 2022 (bottom). Hiring programs from the past decade explicitly prioritizing activists (often created with the intent of skirting civil rights laws) may explain the large increases between these years in some traditionally non-politicized fields such as the hard sciences.

Regardless of the causes, it’s worth asking: what would a Biden or Harris administration do if they discovered that 40% of university faculty identified as one of: “reactionary”, “freedom fighter”, “fascist”, or “Christian nationalist” (the rough conservative equivalents of the categories above)? Would they really hem and haw and wax poetic about academic freedom? I’m not sure that they would, even if that was ultimately the right thing to do given the importance of academic freedom to universities’ functioning.

Universities—despite purportedly dedicating themselves over the past decade to eradicating bigotry and promoting emotional well-being—have become national epicenters of bigotry and mental illness. Honestly, this is one area where my impression is that the reality on many campuses is actually worse than most Americans realize. For what this looks like in general, I recommend John McWhorter’s Woke Racism (on bigotry) and Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt’s The Coddling of the American Mind (on links between prevailing ideological narratives and habits of mind conducive to anxiety and depression).

For what it looks like in the education field (and other adjacent fields), I recommend Chris Rufo’s America’s Cultural Revolution. Love or hate his book’s overall thesis or his scorched-Earth approach to the culture wars, his documentation of the ideas of foundational education scholars like Paulo Freire—extensively quoting these scholars’ own words—is frankly shocking to the uninitiated. As The Atlantic’s Graeme Wood describes (in a somewhat negative review of Rufo’s book): “Freire called Mao’s Cultural Revolution ‘the most genial solution of the century,’ a line that sounds, when applied to mass starvation, straight from the mouth of Lex Luthor…yet his book Pedagogy of the Oppressed is taught in every education school in America.” Mao may have been the deadliest dictator in world history, responsible for tens of millions of deaths. Pedagogy of the Oppressed—which argues that teaching children revolutionary politics is more important than basic facts, and that political violence by “the oppressed” creates “love”—has over 130,000 citations, according to Google Scholar, making it one of the most-cited works in the history of academia. It certainly has a place in the scholarly library as a feature (and cautionary tale) of intellectual history, but its place at the center of the canon is damning.

Again, it’s worth considering a close hypothetical analogy, with the political poles reversed: what would a Biden or Harris administration do if they discovered that the most-cited works in the education field were written by literal Nazi sympathizers, whose most influential ideas were directly connected to their Nazi sympathizing? Would they really hem and haw and wax poetic about academic freedom?

It’s not just Freire. I don’t think most people appreciate how much casual and explicit support there is for bigotry and discrimination, political violence and extremism, and some of history’s deadliest autocrats, in the North American education canon. Reports of how these ideas have been applied to promote racialized nihilism and antisemitism in some of today’s K-12 schools trouble me deeply as a parent (especially as a parent of multiracial children). So do surveys (summarized here at 54:03) finding that most schools of education do not teach the cognitive science of how children learn to read, including the role of phonics and other foundational skills.

For psychotherapy—and how many schools are now teaching their students to racialize their patients and prioritize radical political goals over their patients’ well-being—I recommend Greg Lukianoff and Rikki Schlott’s relevant chapter in The Canceling of the American Mind and Abigail Shrier’s Bad Therapy. Again, what they describe is so bad, and so insane, that I wish it were harder to believe than it is.

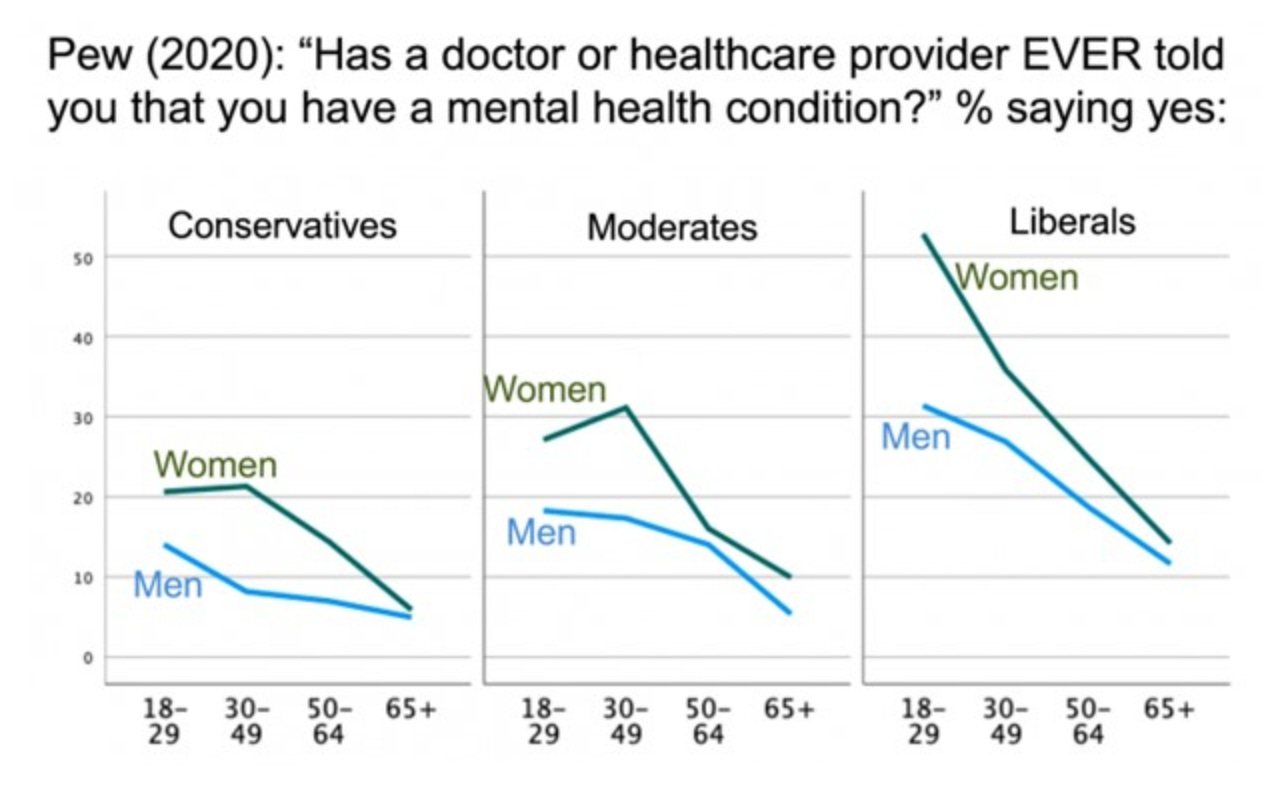

If the average American knew the common curricula of some of these disciplines, I think they might have been less surprised to see things like dozens of professors openly praising the October 7 attacks (in some cases before Israel had even retaliated), or the stunning rates of mental illness that have emerged among politically liberal young women (see below and here). Remember, these are some of the same professors who told us for years that ‘microaggressions’ were a form of violence.

At least two studies have found that exposure to common ‘social-justice’ narratives in academia is associated with increased willingness to endorse Hitler-derived statements about groups deemed “oppressors” (Jews, whites, Indian Brahmins). In a recent Washington Post article, Megan McArdle described how a 2020 CDC vaccine advisory panel recommended prioritizing race over vulnerability in the COVID-19 vaccine roll out, despite their own models projecting that this would cause thousands of additional deaths. In other words, some schools are training people in our most important professions to be so committed to racial preferences that they are willing to knowingly sacrifice thousands of their fellow citizens’ lives. One doesn’t have to be a fascist, authoritarian, or whatever else people want to call President Trump, to see that there are serious problems here.

Universities’ enrollments, and their graduates’ job prospects, are suffering as a result of these problems. As I mentioned above, U.S. universities are losing enrollments faster than falling birth rates alone should have caused. The share of high school graduates attending college has dropped steadily over the past decade (during the Great Awokening period), and the drop is especially pronounced among young men (see below), who increasingly reject universities’ dominant ideologies.

Employers are also increasingly saying that they will shun graduates from universities that they perceive to be captured by the pathologies I describe above. Unemployment rates for recent U.S. college graduates have skyrocketed compared to the national average (see below) since the early 2010s. It’s not clear how much universities’ trust issues contribute to this compared to other factors like the post-financial-crisis economy and emerging artificial intelligence (AI). But it’s worth noting that the timing of graduates’ employment challenges—like the enrollment slides—coincides quite closely with the universities’ Great Awokening and their corresponding trust problems (see graphs above and below).

I could go on, but hopefully I have made my point that universities have both enormous value to American society and enormous problems urgently needing reform. The American public—and by extension the American government—has a large stake in fixing the problems while preserving the value. Any approach to reform by the federal government that doesn’t respect universities’ enormous value to society, and any response to the federal government by universities that doesn’t acknowledge and address universities’ enormous and festering problems, isn’t serious and is doing a major disservice to the American public.