How polarization will destroy itself

Political polarization and extremism are much more fragile than we realize, as long as we maintain freedom of speech, rule of law, market competition, and free and fair elections.

As an economist, I’m trained to look for bad incentives when society has a problem. Political polarization is a huge problem in this country, and, sure enough, there are lots of bad incentives. Money in politics rewards pandering to the rich. Partisan primaries with low turnout, and increasingly uncompetitive gerrymandered congressional districts, reward extreme politicians. Social media algorithms reward outrage, tribalism, and extremism. Subscription-based online and cable news reward echo chambers. Incentives to please peers, get attention, and publish significant results in academia reward groupthink, sensationalism, exaggeration, and performance.

How do we dig ourselves out of this mess?

Over the past few years, I’ve come to believe that there is a surprisingly simple answer: these polarizing incentives will be fragile as long as we make sure that our core democratic institutions hold. Specifically, if we can maintain free and fair elections, freedom of speech, market competition, and the rule of law, the polarizing forces in our society will eventually undermine themselves, and the silent, exhausted majorities will eventually hold them accountable. Think of polarization as a very bad flu, and our democratic institutions as our immune system. We are pretty sick right now, but our immune system will eventually win as long as we don’t become immunocompromised.

Not only do I think that our institutions are strong enough to beat polarization, I think this is already starting to happen, slowly but surely. Of course, we should still remain vigilant and protect our institutions. This includes teaching our children why these institutions are so important, and how bad things can get if we lose them.

Polarization is like hard drugs.

Hard drugs disproportionately draw people in who are aggrieved, and then provide them with a simple solution to their problems and a steady stream of dopamine hits. But hard drugs ultimately make their users miserable; they make their users’ personal problems worse, not better; and they create economic and quality-of-life problems for everyone else that societies eventually refuse to tolerate, no matter how compassionate the societies initially are towards the drug users.

For example, Oregon’s legislature recently voted to re-criminalize possession of hard drugs. Politicians in other historically permissive progressive strongholds—Seattle, San Francisco, Oakland, and Los Angeles, among others—are facing backlash over crime, homelessness, and open-air drug abuse.

That doesn’t mean that drug abuse will be easy to eradicate from society altogether. Indeed, it remains a huge, huge problem in America today. But it does show that voters will eventually force politicians to rein it in, no matter what their other incentives are.

Polarization is similar. It draws people in who have real grievances, like de-industrialization, socioeconomic and racial inequality, lack of respect from elites, stagnant real wages, and declining American power, to name a few.

Polarization offers easy answers to these problems. If we cut enough environmental regulations, coal will come back. (It didn’t.) If we demonize and defund the police, that will help the Black community. (It didn’t, and most of the Black community never wanted to defund the police in the first place.) We should not get the COVID vaccine because the medical establishment—who suppressed information about masks, the possibility of a lab leak, and the economic and human costs of lockdowns—can’t be trusted. (The medical establishment did suppress information, but vaccine hesitancy still cost thousands of disproportionately Republican lives.) Getting people to identify themselves as victims will help them overcome disadvantage. (Actually, research suggests it is more likely to harm their mental health and promote narcissistic and antisocial behavior.) If we own extremists on the other side enough, they will lose their power. (Actually, extremism on one side increases the power of extremism on the other side. More on this below.)

Polarization also offers dopamine hits. Who among us has never felt that tinge of schadenfreude when someone really awful or annoying on the other side got dunked on or canceled?

But polarization also makes worse the very grievances that it draws its power from. For this reason, voters and citizens will eventually reject it, as long as they retain the freedoms they need to make that choice.

Slowly but surely, this is already starting to happen. But again, there are things we can do to make it happen faster.

Division and extremism don’t make America great.

As President Lincoln once said, paraphrasing Jesus (according to Matthew, 12:25): “A house divided against itself cannot stand.” How is a divided society supposed to have a healthy democracy? How is a divided society supposed to remain the envy of the world—the ‘shining city on a hill’? How is a divided society supposed to be able to recruit enough of its young people to join the military to keep it strong? How is a distrustful society supposed to maintain healthy commerce and capitalism?

Storming the Capitol to stop the peaceful transfer of power, and undermining the public’s faith in elections, don’t strengthen or honor the US constitution. Casting aspersions on decades-old western alliances and cozying up to hostile foreign dictators like Vladimir Putin and Kim Jong Un doesn’t improve America’s (or the west’s) place in the world. Siphoning millions of dollars, from the political party that claims to represent Christians, to pay legal bills covering for someone’s—frankly, sinful—misdeeds (someone who is now literally selling Bibles to help pay these bills), doesn’t honor Christianity. Idolizing that person (or anyone for that matter) doesn’t honor Christianity either. State and local governments rejecting billions of free federal dollars that would expand healthcare (Medicaid) or create thousands of well-paying union jobs in emerging clean energy industries doesn’t help communities facing de-industrialization. Tax cuts for the wealthy aren’t going to fix the federal debt problem. Sowing chaos within the Republican party Congressional caucus doesn’t strengthen the party or the country.

At some point conservatives, Christians, and patriots are going to look at the extremists on the right and start asking themselves: Are we really going to keep letting these people wrap themselves in the American flag and the Bible, and claim that they own both? The answer will eventually be ‘no’.

Slowly but surely, this is already starting to happen.

For example, President Trump lost the 2020 election to Joe Biden, and left office with the lowest approval rating at the end of is presidency of any president since Truman in 1953. In the 2022 midterm elections, Republican candidates supporting the false claim that the 2020 election was stolen from Trump disproportionately lost to Democrats in competitive races. Firebrand Lauren Boebert—running in a district (CO-3) that was supposed to be safely red—won by only ~550 votes. Despite its currently high market valuation as a meme stock, Trump’s Truth Social platform has only 1 million active users and loses tens of millions of dollars annually (which will eventually bring its stock back to Earth).

Sensing that voters are tiring of brinksmanship and dysfunction, Republicans in Congress have consistently passed continuing resolutions to fund the government during the Biden administration, avoiding government shutdowns that were previously a common threat. The members who ousted Speaker Kevin McCarthy have been shunned by donors and face primary challenges.

Republicans, responding to their base, have also started to shift their economic policies towards more skepticism of consolidated corporate power and towards more support of the social safety net. Legislators like Josh Hawley and J.D. Vance—hardly moderates—have worked with Democrats to support banking regulation and antitrust. Donald Trump opposes cutting social security to reduce the deficit, and even stated support for universal healthcare at times during his 2016 campaign (though later supported repealing Obamacare).

Of course, extremism is still a powerful force on the political right and in the Republican party. For example, almost all of the members of Congress who voted to impeach President Trump over January 6th have since left or been pushed out of politics. Most Republican politicians—including many who disavowed Trump after January 6—now endorse him for President in 2024. Far-right media outlet Newsmax has higher ratings than CNN in some key time slots.

As I will explain in more detail below, the strength of the far right in the United States lies in numbers—it includes a sufficiently large fraction of the Republican party’s base to be a potent force in primaries. But the far-right’s weakness is its lack of appeal and lack of power outside of that base. The far right cannot win general elections without help from moderate conservatives and independents, and the far right has almost no power in mainstream cultural and educational institutions, aside from those they create specifically for themselves. The far left has opposite strengths and weaknesses. For this reason, my best guess is that the far left will be resoundingly defeated first in politics and culture, and afterwards the far right will be defeated, once they have only paper tigers left to fight. More in this below.

Division and extremism don’t make America just or equitable.

All of the big societal problems that progressives claim to want to solve—like inequality, lack of healthcare, poor education outcomes, and environmental problems—require public goods provided by the government, cohesive civil societies, or both.

The clear conclusion of decades of research in political science and economics (summarized, for example, here, here, and here) is that people within a society need to have a strong shared sense of identity to be able to politically and civically support public goods provisioning. So, the far-left’s tactic of dividing people into ever smaller identity groups, encouraging them to segregate themselves, and pitting them against each other, is extremely unlikely to lead to anything resembling progress on the problems the far left claims to care about.

Relatedly, decades of psychology research shows that adopting a victim mindset is associated with poor mental health and narcissistic and antisocial behavior. So, the far-left idea that teaching people to see themselves as victims will somehow empower them, or lead to a more cooperative, fair society, is also deeply misguided.

Lastly, the pessimistic environmentalism of the far left—which casts humanity as a plague and calls for de-growth and not having children to protect nature—is so transparently anti-human that it will never be widely accepted by, well, humans. Visions of environmental progress that either explicitly or implicitly require poor countries to stay poor will also be shunned by developing-world leaders, and will eventually also be shunned by progressives who see the injustice in developing world poverty.

So-called ‘social-justice’ progressives have pushed police demonization and permissive criminal justice policies since 2020 that have caused violent crime to spike and businesses to flee the very disadvantaged communities they claim to be helping. They pushed long-term school closures during COVID, and other misguided education policies, that have contributed to record absenteeism and widening of achievement gaps, again harming the most disadvantaged communities the most. Permissive border policies are causing sanctuary cities to buckle fiscally and socially. Not-in-my-backyard (NIMBY) obstructionism is making housing affordability crises worse and preventing progress on decarbonizing the economy. Victim-fetishizing therapy cultures have contributed to record mental-illness rates among politically liberal women and girls. And teaching young people in K-12 and universities to see everything in the world through the lens of racial and ethnic identities, and oppressor-oppressed grievance binaries, has helped to create the vile antisemitism that exploded into the public eye since October 7, 2023.

At some point, liberals and progressives who care about results (more than performative posturing) are going to look at the extremists on the left and start asking themselves: Are we really going to keep letting these people pretend that they are the champions of the marginalized, anti-racism, emotional well-being, kindness, and the environment? Again, the answer will eventually be ‘no’.

Slowly but surely, this, too, is already starting to happen.

The far-left’s biggest weakness is its numbers. One survey estimated that it makes up about 8% of the electorate—a small minority even among Democratic voters. The far left’s biggest strength is the amount of influence it has in academia, big tech, mainstream media, advocacy organizations, and other important cultural institutions (the ‘symbolic capitalist’ professions, as the sociologist Musa al-Gharbi calls them). So, the far left can make a lot of noise and influence the culture, but they ultimately cannot overcome the unpopularity of their ideas, as long as markets, speech, and ballot boxes remain free to reveal that unpopularity.

Politicians representing the ‘social-justice’ left are great at losing elections, even primaries in Democratic strongholds. For example, they lost major primaries in New York, Minneapolis, and nationally in 2020 and 2021—the height of the post-George-Floyd social-justice movement. They have lost to Republicans in Seattle, and faced recalls in San Francisco and Oakland. And they have increasingly been blamed by other Democrats for the party’s poor national performance and polling against a Republican party that should be very beatable.

The far left’s unpopularity makes their hold on cultural institutions fragile, too. Their takeovers of academia and mainstream media have caused trust to crater in both. Their influence on major corporations has caused major public embarrassments for some (e.g., the launch of Google Gemini), and large financial losses for others (e.g., Bud Light). When they use movies and other forms of art to push their agenda, those forms of art tend to tank in the box office. Many non-profit organizations that were taken over by the extreme left post 2020 have seen high staff turnover, governance problems, and cratering donations. Several media outlets taken over by the extreme left went out of business (or may be about to go out of business), including Deadspin, Buzzfeed News, Gawker, and Guernica, to name a few. The saying, “get woke, go broke,” is crass and off-putting, but it seems to have a grain of truth to it.

The extremes are each other’s best friends.

The greatest lie that people on each extreme tell everyone in the middle is that they are the answer to the other side’s extreme. In fact, the extremes help each other in two ways.

First, each extreme provides a bogeyman that energizes the other extreme. The so-called ‘Great Awokening’—the rise of cancel culture and identity politics on the left—began around 2013-2014. Many analysts believe that backlash against the start of the Great Awokening helped Donald Trump get elected in 2016. Of course, Trump’s election didn’t stop the Great Awokening, it supercharged it. Having an openly misogynistic, xenophobic, norm-breaking, and anti-democratic President galvanized the far left, and enabled them to tighten their grip on sense-making institutions in media and education that had previously been axiomatically non-partisan. Since 2020—when Joe Biden was elected—there have been signs that the Great Awokening is winding down.

I vividly remember a conversation I had with a good friend of mine—at that point a never-Trump Republican—in July 2020. The violent protests in response to George Floyd’s murder had already happened, and Trump was still in office. My friend had voted for Gary Johnson in 2016—not wanting to vote for either Trump or a Democrat. He said to me that he was thinking of voting for Trump this time, in 2020. When I asked him why, he said something like, “I still don’t like Trump, but I’m just so scared of all this woke stuff.” I responded with something like, “It sounds like you think that, if Trump was President, we wouldn’t have this woke stuff.”

The second way the extremes help each other is by each silencing the moderates on their own side. (Social media makes this easier.) This pushes each side’s moderates into the arms of its side’s extreme, by making them think the two extremes are all they have to choose from. There are a lot of Democrats who don’t like the far left, but who will choose them over candidates like Trump. There are a lot of Republicans who don’t like Trump, but would choose him over a candidate that seemed to be too soft on crime, too soft on illegal immigration, or too radical.

How extremism will eventually be defeated

In business, culture, and education, both extremes will eventually be defeated by the market. Consumers will reward companies that stay out of the culture wars, focus on product quality, and market to the widest possible range of consumers. “Republicans buy sneakers, too,” as Michael Jordan famously said. Audiences will reward entertainment that is fun to watch, even if it is not politically correct. Students and parents will reward schools that prioritize math and reading and other key competencies. If public K-12 schools aren’t willing to prioritize these things, students and parents will turn to charter schools, private schools, and homeschooling, and they will vote for politicians that make these options available. If universities are not willing to prioritize teaching core competencies and truth-seeking in research, and if they keep wasting their money on politicized and ineffective administrative bureaucracies, universities will continue to lose enrollment and face attacks from legislators.

In politics, my best guess is that the far left will be defeated first, from within the Democratic party. Moderates and conservatives make up a majority of Democrats, while most Republicans identify themselves as conservative or very conservative (see below). So, it will be easier for moderate Democrats to defeat far left—who are usually a minority of Democratic primary voters—than it will be for Republicans to defeat the far right—who are sometimes a majority of Republican primary voters. However, once the far left is defeated, the newly moderate Democrats will hand the Republicans enough embarrassing general-election defeats to inspire the Republicans to sideline their extreme factions. Famed political scientist Francis Fukuyama has made a similar prediction, drawing parallels to the polarization of the late 1800s.

The far left’s excesses also arguably have the potential to cause more local, immediate, and acute quality-of-life issues that affect broad swaths of the electorate (high crime and illegal immigration, expensive housing, high taxes and interest rates, inflation, division and dysfunction in schools), and therefore they may provoke a stronger, more immediate responses.

In contrast, the far-right’s most unpopular excesses tend to either acutely and immediately affect a relatively small number of people (e.g., women actively seeking abortions) or have abstract and longer-term effects. For example, things would eventually get really bad if Donald Trump succeeded in undermining our democracy, and we should all be very concerned about that. But, even on January 7th—the day after arguably the worst attack on our democracy in at least a generation—the average person’s life was no different than it was on January 5th. Similarly, risky banking deregulation eventually caused a major global recession (in 2008), but it took years for the housing and asset bubbles to form and then burst. And failing to address climate change could eventually lead to catastrophic consequences, but we won’t see most of those consequences this year. None of this is to say that the far right is ultimately any less harmful than the far left. It’s just to say that their harms may be less immediate and acute, and therefore less salient to the average, non-politically-engaged voter.

I’m open to the possibility that I’m wrong in stating that the far-left’s costs to society are more immediate, acute, and broadly felt than the far-right’s costs to society are. But if I’m right about this, it would support the prediction that voters and markets will be motivated to defeat the far left first, after which voters will have more intellectual bandwidth to defeat the far right. This prediction may help to explain the fact that Trump leads Biden in many recent polls, illegal immigration is currently the most important issue for voters, and yet Trump also has high unfavorables and is struggling to get small political donations (which suggests that his popularity is softer than his head-to-head polling numbers). To be clear, this is not an endorsement of Trump for President. I consider Trump to be temperamentally unfit for office; Biden has governed from the center more than is reported or than he gets credit for; and misguided progressive local policies mostly aren’t Biden’s fault. It’s just a hypothesis about why Trump may be polling so well in spite of his shortcomings.

The fragile incentives for polarization

If polarization is on its way to resolving itself, what about the incentives for extremism that I listed at the beginning of this essay? Let’s take another look at each, this time recognizing its fragility.

Money in politics rewards pandering to the rich. True, but the rich are a small minority of voters, and an increasingly democratized, accessible information landscape makes pandering to the rich harder to hide from voters. Look at how the Republican party has slowly shifted to the left on economic policy over the past decade. In fact, political campaign spending often has relatively small effects on electoral outcomes, especially for candidates with high name recognition, like presidential candidates. The 2020 California ballot measure to reinstate affirmative action illustrates this: it failed, despite the pro side having a 19-to-1 spending advantage and endorsements from most major institutions.

Partisan primaries and increasingly uncompetitive, gerrymandered congressional districts reward extreme politicians. True, but winning presidential, Senate, and gubernatorial elections still require winning moderates. For Democrats, even safe blue districts may not be winnable at the primary level for extremists. Perhaps for these reasons, a recent study found that primaries do not, on average, have a large polarizing effect on the voting records of members of Congress.

Social media algorithms reward outrage, tribalism, and extremism. True, but constant outrage and tribalism also make people angry and miserable, and corrode civil society. Some users will eventually get fed up and leave the platforms—shrinking their user bases—and the harmful effects of social media on society will attract bipartisan regulatory scrutiny.

Subscription-based online and cable news reward echo chambers. True, and this may be somewhat of a good business model in the long term for outlets serving the far right. But it is not a good business model for most outlets serving the far left, and it is a terrible business model for mainstream outlets whose brand is based on trustworthiness of their news.

Incentives to please peers and get attention in academia reward groupthink, sensationalism, and performance. True, but academia is ultimately dependent on demand from students and their parents, and on massive public subsidies in the form of grant dollars, financial aid, and tax exemptions. Students, parents, and governments will not put up, for very long, with academic institutions that subordinate their truth-seeking and skill-building educational and research missions to intellectually vacuous ideological pandering. Once the losses of trust and enrollment become clearly an existential threat to universities’ continued survival (which is already starting to happen), university leaders will grow a backbone and both rein in their out-of-control administrative spending and stand up to their ideological elements (whom they and most faculty and students already strongly dislike anyway, in my experience, because of these elements’ self-righteousness, vindictiveness, intellectual vacuousness, and all-around cringe-y behavior).

Additionally—in defense of present-day academia as it is—most academics still socially value accuracy as part of their vocational identity, even in academic fields with highly skewed political demographics and some political biases. As a result, blind peer review (where reviewers are anonymous and can state their opinion free from threats of public sanction) tends to be less politically biased than most academics imagine.

Our democratic institutions (actually) make America great.

Political polarization is a major problem caused by bad incentives. Economics teaches us that, if we have a major problem caused by bad incentives, we need institutions to provide better incentives in order to fix the problem. If that’s true, how can I be claiming in this essay that polarization will eventually fix itself without major new institutions?

The answer is not that I think we don’t need any institutions to solve this problem. (I am an economist, after all.) It’s that I think we already have the major institutions that we need to solve the problem, as long as we can protect and preserve them. The institutions that we need are the core institutions of western liberal democracy: free and fair elections, freedom of speech, market competition, and the rule of law.

Free and fair elections allow us to throw politicians we don’t like out of office, and to send messages to others. Voters fed up with political correctness and aspects of globalization (offshoring, illegal immigration, etc.) elected Trump in 2016. Voters fed up with the chaos and norm-breaking of Trump’s term in office elected Biden in 2020. Voters fed up with ‘stop the steal’ election lies defeated candidates like Kari Lake and Blake Masters in 2022. Voters fed up with lawlessness in progressive cities recalled San Francisco District Attorney (DA) Chesa Boudin in 2022 and elected a Republican DA (Ann Davison) in Seattle in 2021.

Free speech and market competition allow us to eventually sort good ideas from bad ones, and good sense-making institutions from bad ones, even if it’s a messy process that takes a while.

Left-wing cancel culture, as bad as it was (it may have wrecked more careers than McCarthyism), did not stop far-left ideas from becoming widely unpopular, nor did it prevent entrepreneurs from starting popular and enormously profitable counter-cultural institutions. Consider the fact that 12 Rules for Life by Jordan Peterson—the ‘professor against political correctness’—has spent 317 consecutive weeks on Amazon’s non-fiction best-seller list and is one of the all-time best-selling books by an academic. Or consider the fact that the country’s most popular podcaster is Joe Rogan.

Platforms like Substack have allowed for new media outlets to proliferate in areas where there seemed to previously be ideological gaps or major stories uncovered. Innovations like X’s (formerly Twitter’s) ‘community notes’ feature have the potential to democratize fact checking—making it less prone to ideological bias—without loss of accuracy.

The backlash against left-wing identity politics and cancel culture may have fueled the rise of Trump and Trumpism, but it did not prevent social norms and public opinion from continuing to turn against discrimination and explicit prejudice against racial minorities, women, and sexual minorities. Nor did it stop actual prejudiced behavior against these groups from decreasing (and, in some cases, reversing) over the long term. Backlash against the excesses of the #MeToo movement did not generate any sympathy for the worst workplace-sexual-harassment offenders, like Harvey Weinstein, who remains in prison.

After George Floyd was murdered in 2020, and the country turned its attention to persistent racial inequality, market competition fueled the rise of corporate DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusion) programs. Then, as it became clear that many DEI programs were enacting illegal racial discrimination and promoting unscientific racial stereotyping, and governments in several states started enacting legislation opposing them, companies scaled back their DEI programs. Similarly, corporate ESG (environmental, social, and governance) programs proliferated as consumers became more socially conscious and there seemed to be a benefit of ESG to investors’ bottom lines. Some ESG programs were then scaled back in response to threats of state regulation and antitrust exposure. Some research also suggests that the financial benefits of ESG investing may have been overstated. Yet, companies’ environmental standards have continued to improve, on average.

Currently, different states and localities are experimenting with different approaches to regulating K-12 schools, universities, and investors. Some appear to be injecting left-of-center politics into these institutions; others appear to be injecting right-of-center politics; others are promoting more neutral or hands-off approaches. States and localities also differ in their approaches to crime, abortion, construction, taxes, and other issues. Competition for students, people, and capital between these states and localities will eventually send market signals regarding which models citizens prefer. This will provide incentives for states, localities, and institutions losing out to course correct.

Rule of law (and laws that are impartial) provide a final safeguard, and a check on even concentrated executive, corporate, or majoritarian power. Trump was not only unable to stop the peaceful transfer of power in 2020-2021, he may end up going to jail for trying. Companies and educational institutions who fired people without cause as part of cancel culture, or who illegally discriminated on the basis of race or gender in hiring, are facing (and losing) multimillion-dollar lawsuits and civil rights complaints. The US Supreme Court is considering a case against the federal government for encouraging social media platforms to suppress speech. There is a bipartisan effort to pass new legislation to rein in the most harmful aspects of social media.

None of this means that elections, markets, marketplaces of ideas, and the legal system will get things right immediately. It’s messy. Pendulums can swing too far one way and then swing back too far the other way, at least in some respects. But elections, markets, and marketplaces of ideas do allow moderate majorities to check extremes’ power—and the rule of law protects everyone’s rights, including minorities’ rights—in ways that citizens of authoritarian countries can only dream of.

It is impossible to overstate how much our democratic institutions prevent us from going off the rails, compared to what happens in authoritarian societies. For example, some critics compare extremes of wokeness to the Chinese cultural revolution. Yet, wokeness has peaked less than a decade after it arose, and killed very, very few people. Chinese communism lasted decades and killed millions. Similarly, some critics of Trumpism compare it to ethno-fascism, but even Trump’s Republican party shuns politicians and staffers over explicit displays of racial animus, presumably at least in part because they fear the unpopularity of these positions with voters.

Francis Fukuyama famously predicted in the 1990s that the superiority of these democratic institutions of the west (free speech, free and fair elections, market competition, and the rule of law), compared to their alternatives, would cause western-style liberal democracy to proliferate throughout the world, leading to the “end of history”.

History of the past 30 years has proven Fukuyama’s thesis wrong in some respects. Authoritarian forms of government have been durable in many countries, including in China and Russia, which have become more authoritarian over the past ten years after somewhat liberalizing in the two prior decades. Democracies—especially younger ones, like Hungary’s and Turkey’s—have also proven susceptible to anti-Democratic drifts. And even mature democracies like the United States’ have faced threats in the past few years not seen in decades prior.

However, Fukuayama’s thesis has been proven right in important ways, too. For example, turning away from democratic institutions has ended up stifling China’s and Russia’s economic rise compared to the U.S. The more democratic India now has much faster GDP per capita growth than both China and Russia, and it has dramatically reduced extreme poverty. As scary as some of the recent anti-democratic pivots of the political extremes in established western democracies have been, our institutions have so-far withstood them.

In fact, I would go so far as to say that our institutions have withstood these threats with flying colors. For example, the January 6th riot—when viewed as a symbolic attack on our democratic norms—was no-doubt a generational blow to our national psyche. But, if viewed as an actual attempt to overthrow the government, it was a pathetic, disorganized failure. Similarly, brief attempts on the far left to upend the rule of law (e.g., the autonomous zones in Seattle and Minneapolis, and the ‘defund the police’ movement) also quickly ended in failure, in some cases being reversed by the very same politicians who had enabled them weeks earlier. Efforts to suppress voter turnout for partisan gain have tended to backfire. Attacks on freedom of speech have been more pervasive and long-lasting, but even these are now in retreat.

Nonetheless, we should remain vigilant in protecting and preserving our core democratic institutions. We should not tolerate politicians who disrespect these institutions, even if they come from our own side of the aisle. We also need to teach our kids about these institutions and why they are important. It is concerning, for example, that support for free speech and democracy is declining generationally.

Conservatives who want to promote American greatness should remember that our democratic institutions—free and fair elections, freedom of speech, market competition, and the rule of law—are what make us great. Liberals and progressives—who would lecture us on the importance of recognizing and sharing our privileges—should remember that these democratic institutions are our greatest source of privilege. They have also been our greatest sources of progress.

We can make America even better.

Before we declare (or predict eventually declaring) victory against political extremism, it is worth revisiting the real grievances that have fueled it: de-industrialization, socioeconomic and racial inequality, lack of respect from elites, declining real wages, and declining American power.

Because the political extremes are so unhelpful at addressing these grievances in practice, I am optimistic that the extremes will sow the seeds of their own destruction, whether or not we address the underlying grievances. But I also think we could speed up the process of depolarizing our society by making progress on addressing these grievances.

Obviously, laying out how we can address each of these complex issues is too large of a topic for the tail end of one essay. Each issue requires its own conversation and its own process of cooperation, experimentation, and iteration. In many of the areas, I may not be enough of an expert to meaningfully participate.

Instead, I will offer three general observations.

First, attempts to address complex societal issues will not be successful unless they are serious. By serious, I mean rigorous and evidence-driven, thoughtful, and pragmatic. By pragmatic, I mean more focused on delivering results than on pieties, purity tests, or political posturing; and ambitious, but also aware of and concerned with practical limitations. Any approach that is not serious does not deserve to be taken seriously. Any activist or pundit who tries to gain status by pushing an approach that is not serious does not deserve to be taken seriously either. Let’s treat these issues with the respect they deserve, and let’s not put up with any more charlatans who would disrespect the seriousness of these issues.

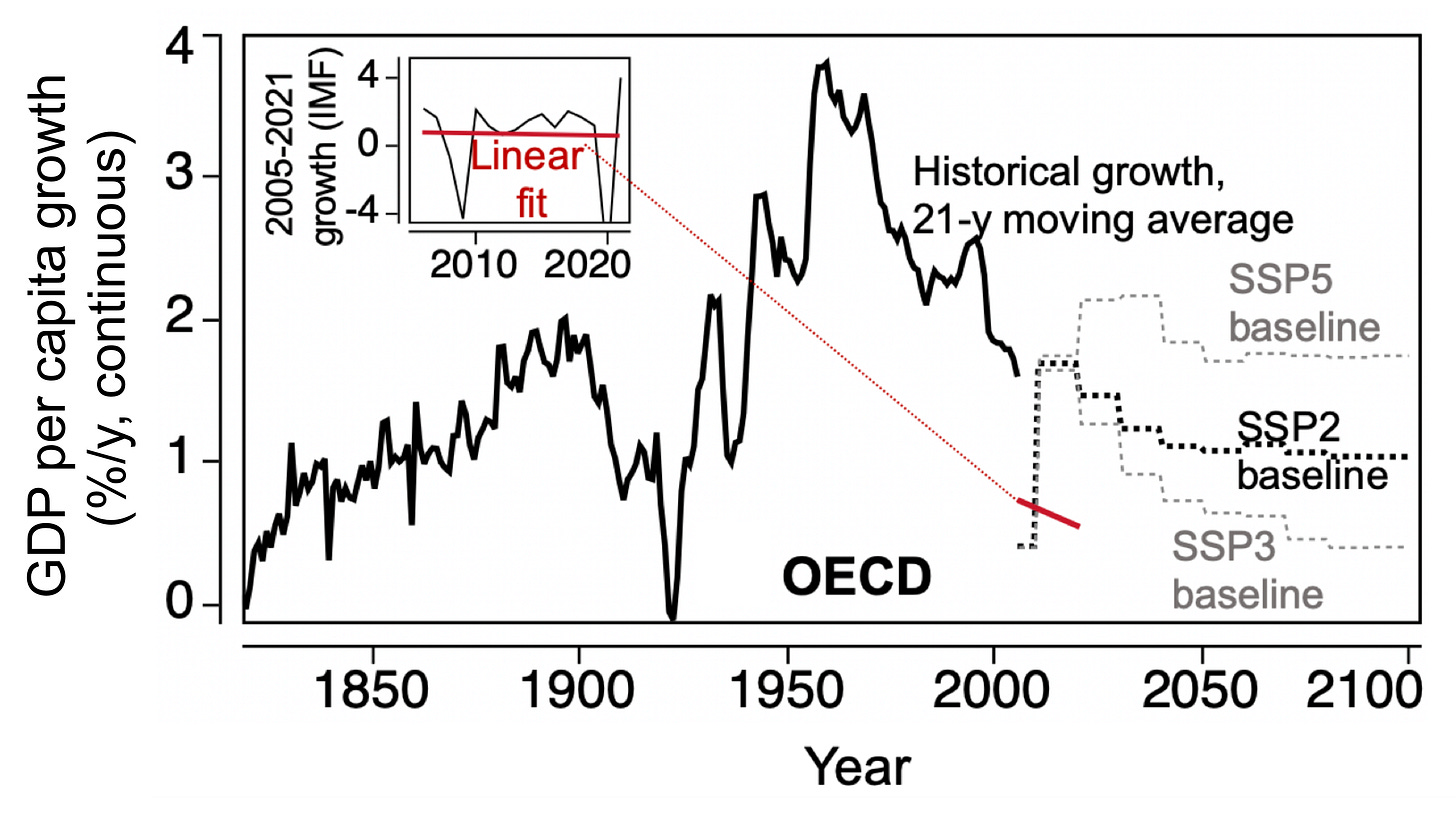

Second, slowing economic growth will make reducing polarization, and solving the underlying societal problems, harder. GDP per capita growth has been steadily slowing the United States and other developed countries since the 1960s. Many economists think growth will continue to slow for the foreseeable future—whether we want it to or not—because of aging populations, shifts towards service-oriented economies, and other factors that are more context dependent like public and private debt levels. Slowing economic growth has the potential to create zero-sum mindsets (which catalyze polarization), gaps between expectations and reality for young people (which catalyze social and political unrest), and a variety of other social, economic, and political problems. It is possible that artificial intelligence (AI) or some other technological breakthrough will reverse this trend of declining economic growth, but we should prepare for the possibility that it doesn’t, just in case.

Third, we need to build a strong, shared, multicultural identity.

Our country is very diverse. For example, 14% of the US population was born in another country, and 42% of the population (and 53% of those under 18 years of age) identify themselves as non-white, Hispanic, or multiracial. So, we will be a diverse country, and we will continue diversifying, regardless of what our policies on immigration or border security are. Those on the political right who lament our country’s diversity need to accept that our diversity is now intimately, unavoidably, and irreversibly linked to our national identity. It’s part of our DNA.

Our diversity gives us lots to be proud of. Our ability to attract and welcome top talent from all over the world is a big reason why we are the world leader in innovation, research, and higher education. It is a big reason why we dominate international competitions in sports and many other fields. Immigration is also the main reason that our population is not aging as quickly as those of Japan, South Korea, and other low-immigration peers. The US has seen more than twice as much real GDP per capita growth in purchasing-power-parity terms than Japan has, since 1990 (60% vs. 27%).

However, those on the political left need to acknowledge that, without a shared identity, diversity can pose challenges to our social fabric. American sociologists and economists have often found negative relationships between ethnic diversity and various measures of public trust, civic participation, and public goods provisioning. Although, these relationships may be partly caused by socioeconomic disadvantage among some US minority groups, similar relationships have been found in a wide variety of geographic contexts around the world.

Fortunately, evidence also suggests that we can overcome the sociopolitical challenges of diversity. Integration eventually leads to increases empathy through contact, intermarriage, and development of strong, shared multicultural identities. In Canada, a 2013 study found a positive relationship between social-network diversity and trust among young adults, opposite to the negative relationship among older adults that has been found in many other countries. This resonates strongly with my experience coming of age in the young cohort of Canadians that were the subject of this study. Our peers were diverse, but most also grew up in Canada. So, we had a shared, unifying sense of what it means to be a Canadian, which allowed our cultural differences to be enriching and shared, rather than being divisive or balkanizing. The US integrations of mainland-European (Irish, Italian, etc.) and later Hispanic immigrants provide similar positive examples.

We are lucky, in countries like the US and Canada that were built on immigration, to have national identities and origin stories that are already built for diversity. This allows us to cultivate cultures that welcome dual identities (also called ‘super-group identities’)—where we can each have sub-group identities (e.g. Canadian American, Japanese American, Hispanic American), while also strongly identifying with our shared, superordinate identity (American). A dual-identity fosters a shared identity while also not promoting xenophobia in the way that a more monolithic form of American identity might.

But maintaining a strong shared, superordinate identity is key. History suggests that social and political movements, which balkanize us by sub-group and make sub-group identities supersede the shared identity, are likely to undermine our social fabric and our democracy.

For all its flaws, the United States is one of the societies with the most prosperity, safety, innovation, education, and rights for minorities and women in the history of the world. America’s biggest flaws are found everywhere in world history in time and space, and they are almost always worse than they are here now. America’s biggest strengths are relatively unique in world history in time and space.

So, the positive aspects of our society are what truly distinguish us. We should focus on these more. They are what define us. We should also focus more on how much agreement there is across the political spectrum on most of our key values, and even on many policy positions. Even if you think that a large fraction of the country is standing in the way of solving some big societal problem, I ask: what’s your theory of change? Is it really possible, or desirable for that matter, to sideline a large fraction of the country from public life? No, it is not. So, let’s roll up our sleeves, talk to each other, get off of social media, and get to work.

Sadly, it may destroy much more than just itself in the process. Because of the perverse incentives of authoritarianism, it is likely to continue to drive this direction too.