How to bridge the divide on climate change

Summary and video of my recent talk to teachers and educators

Yesterday, I gave the science keynote for the Climate Generation’s Teach Climate Network Summer Institute for Climate Change Education’s North America Cohort. The topic was climate change polarization, where seeds of bipartisan cooperation on climate change can be found, and how to communicate across political divides about climate change. The audience consisted of K-12 teachers and other types of educators. Here is the full recording. I also summarize the key points below.

Bipartisan cooperation on climate is essential, because all of the other options are bad.

If we are really serious about changing all of society—our energy and food systems, etc.—over decades, then there are only three options in a democracy (and only one good option).

Some key facts about U.S. political polarization

There is no axis of animosity greater in the United States today than politics. As measured in terms of people’s negative feelings towards their out-group, willingness to discriminate against their out-group, or unwillingness to associate with them, have their kids marry them, etc., partisan negative polarization dwarfs other types of prejudice (e.g. racial, religious, etc.) in the U.S. today. And it’s not close.

Both political extremes are disproportionately rich, white, and educated, and politically hobbyist. So, narratives that frame extremism of either side as in service to the marginalized, the poor or working class, or diversity, are wrong.

The extreme right has more people in it than the extreme left. The extreme right is therefore more often large enough to win Republican primaries than the extreme left is for Democratic primaries.

Consequently, the extreme right tends to have more power in government, and the Congressional GOP has moved further to the right than Congressional Democrats have moved to the left.

But, the extreme left has a ton of power in major cultural institutions (universities, mainstream media, big tech, corporate HR departments, etc.). This has caused these cultural institutions to shift sharply left over the past decade—a phenomenon some call The Great Awokening. Despite this cultural power though, the left wing of the Democratic party struggles to win elections—even Democratic primaries in strongholds like New York City and Minneapolis—because their ideology is, overall, very unpopular.

The unpopularity of the extreme left also causes public trust to erode in institutions that it is seen to have captured.

The median voter is economically progressive and socially conservative. Elites sometimes like to think it’s the opposite (socially progressive, economically conservative), but that is, in fact, a relatively rare, disproportionately elite (and self-serving) worldview.

This means that the Democrats have a natural advantage in elections run on economic issues, and the Republicans have an advantage in elections run on cultural issues. It also means that GOP elites disproportionately drag their party into unpopular economic vices (e.g. tax cuts for the rich), and Democratic elites disproportionately drag them into unpopular social/cultural vices (e.g. soft on crime, soft on border security, racial discrimination in hiring and admissions).

Most Americans don’t like polarization and want compromise. There is a large scope of widely popular policies, across many issues, that could receive bipartisan support.

Some key facts about U.S. climate change polarization

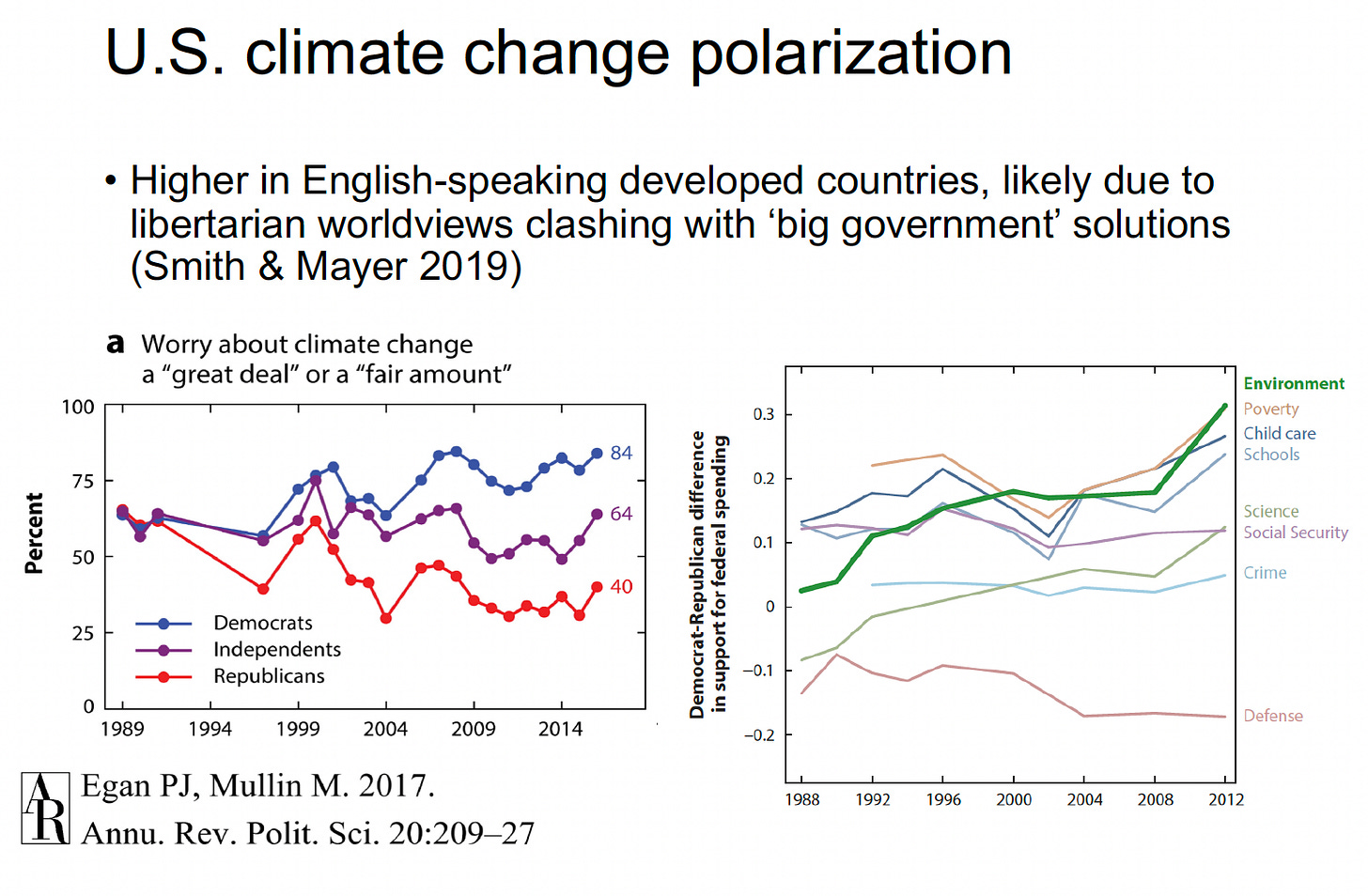

Climate change polarization is relatively recent—it was not a very polarizing issue in the late 1980s. Over the past 30 years, it has gone from being one of the least polarizing issues to being one of the most polarizing issues in the United States.

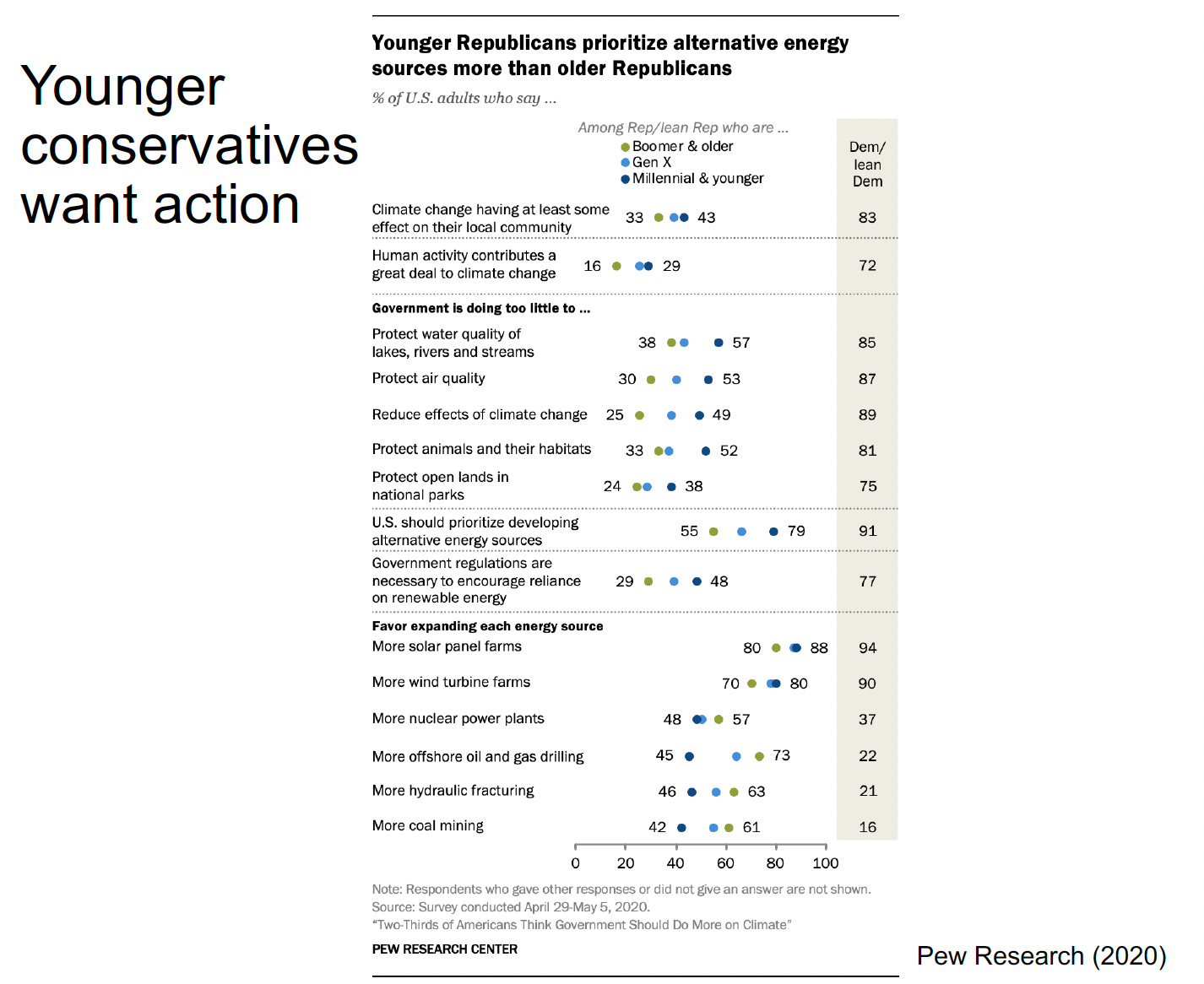

Although it is still polarizing, there are some signs from the past few years suggesting that climate change is becoming a more important issue for a broader swath of voters, and that some actions and policies addressing climate change are gaining large-majority support. This is especially true for younger voters.

As a result, climate change is becoming an election issue for the Republican party. For example, for independent voters, how important they rated climate change as an issue was an extremely good predictor of how they voted in the 2020 Presidential and Congressional elections. As more voters rank the issue as important, the political cost to the GOP will grow, unless they can provide a platform that appeals more to climate-conscious voters than their platforms have in recent history.

Despite the growing consensus among voters for more aggressive climate change policies, there are several remaining political barriers, including: (i) apathy (people often don’t rank climate change highly compared to other issues in their importance), (ii) lobbying and misinformation campaigns fueled by special interests (see the book recommendations below on this), and (iii) the fact that the conservative wing of the Republican party is still quite skeptical of many climate policies and is still powerful in GOP primaries (see above).

Nonetheless, there are also signs of progress, probably driven by: (i) the rising salience of climate change impacts and the rising public concern, and (ii) the improving economics of climate change. For example, renewable energy is disproportionately generated in GOP-controlled Congressional districts, which means that even Democratic climate policies like the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) benefit GOP-controlled districts, which could give these policies staying power.

Key results from my group’s research

In one recent study, we looked at state-level decarbonization bills from 2015, both enacted and failed. We found that nearly one third were passed by Republican-controlled governments and roughly one third were bipartisan.

Bipartisan bills disproportionately expanded choice (i.e. carrots rather than sticks), used financial incentives, and framed efforts to address inequality in terms of economics and not social justice (which we defined as meaning either non-neutrally with respect to race and gender, or using terminology associated with critical theories in academia). This is consistent with other studies, and makes a lot of sense, if you remember that the median voter is economically progressive and socially conservative (see above).

In another study (in review), we conducted a survey experiment looking at how it affected voter support for climate policies when they were paired with other, non-climate policies.

The pairs of policies we used were based on real bills or proposals:

We found that pairing climate policies with pausing EPA regulations (aimed at bringing conservatives on board) did not increase conservatives’ support, but reduced liberals’ and moderates’ support. Pairing with social justice reduced moderates’ and conservatives’ support, without increasing liberals’ support. Pairing with infrastructure did not change support. Pairing with economic redistribution did not change moderates’ and conservatives’ support, and may have increased liberals’ support (not significantly in our study, but another study found a significant gain in support).

Key takeaways so far

The slide below summarizes what I think are the key takeaways, from what we know about polarization and climate politics, about whether to be optimistic about bipartisanship on climate change (yes, we should be! but somewhat cautiously), and about where to find opportunities for bipartisanship. In short, use carrots over sticks, use class/economic frames for inequality-related objectives, and keep climate change as far away from the culture wars as you can. Given that collaborating towards shared objectives reduces inter-group conflict, coming together on climate might help to lower the broader temperature of our politics too.

How to have better climate conversations

Here is advice I give every year, to the students in one of my classes, on how to have better conversations across divides:

Here is some advice I would add specifically for climate change: be precise and stick to the science (e.g., no, your physical climate model does not prove that capitalism is bad); avoid histrionics (performative exaggeration turns people off and makes it harder for people to take you seriously); connect to people’s values and meet them where they are (lots of other folks have given this advice before I have); and be hopeful. Hope is more inspiring than fear or doom.

We have lots of reasons to be hopeful

Being hopeful is consistent with the evidence, as these examples illustrate:

We still live in one of the safest, most prosperous times in human history:

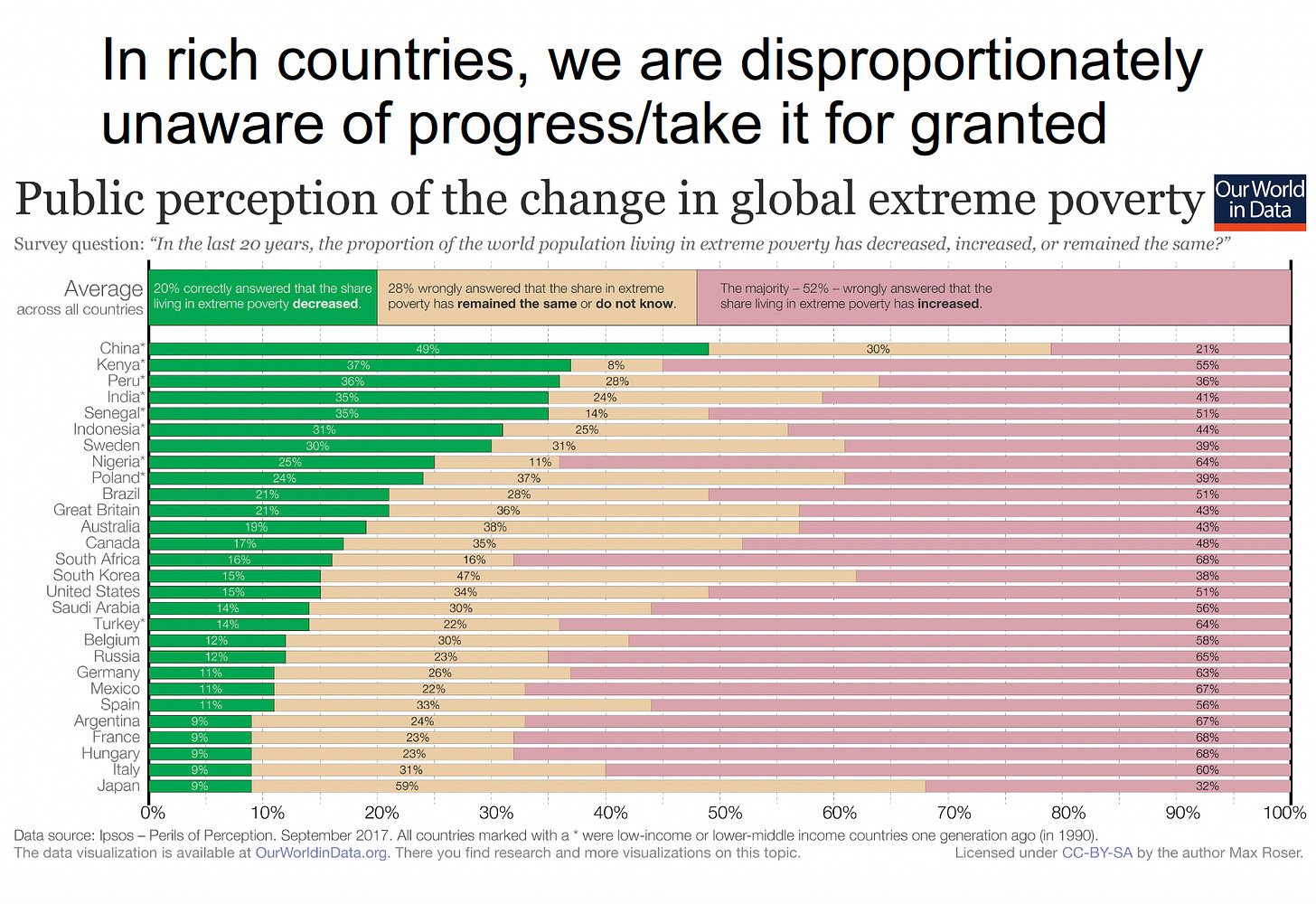

And yet, people in rich countries seem to disproportionately take progress for granted.

Why is that? Partly, this may be because economic growth has been slower in rich countries recently. But I also think this is privilege. Only in rich countries do we have the privilege of ignoring how lucky we are, while we gain status through performances of doomism and fantasies of the apocalypse.

We should also be more patriotic

Social trust and cohesion are extremely important for a society to be able to provide public goods. Providing public goods (infrastructure, new technologies, adaptation and safety nets for people affected) will be a huge part of addressing climate change. Yet, currently in the U.S., concern about climate change is negatively correlated with pride in being American. This needs to change.

Which message is more likely to motivate Americans to address climate change: that we are an irredeemably backwards country with nothing to offer the world besides rapacious capitalism, racism, colonialism, etc.; or that we are one of the most prosperous, industrious, and innovative countries that has ever existed, there is no problem too big for us to solve, and we (not China or the EU) should lead the world in producing and exporting clean technologies? My money is on the second one being more effective (and also more accurate).

Youth mental health is a crisis. Stop feeding it.

Excessive doom and gloom is not a crime whose only victim is the effectiveness of the climate movement. Climate doomism is also probably contributing to the youth mental health crisis.

Youth specifically cite climate change as a major impediment to their mental health, and in the U.S., declining mental health has increasingly become a politically liberal phenomenon. Some experts think this partisan divergence in mental health might be caused by the rise of doomist narratives in online and academic progressive discourse, which emphasize external loci of control and teach unhealthy habits of mind.

So, I urge my colleagues in climate science, as well as journalists and activists, to stick to hope and (in the words of Hannah Ritchie) “stop telling kids they’ll die from climate change”.

Lastly, teach students to be scholars of detail and nuance, not future demagogues.

In my discipline of environmental studies, I worry that we assume that it’s only dangerous to minimize the threat of climate change, and that it can’t be dangerous to exaggerate or catastrophize it. I certainly agree that it is dangerous to minimize the threat of climate change—especially since there are so many low-hanging fruit begging to be picked (cheap renewable energy, nuclear, infrastructure improvements, adaptation, carbon capture, etc.). But catastrophism can be dangerous too, especially if it’s mixed with knee-jerk, tribal solutions.

As my colleagues and I put it in a recent PNAS letter:

“Overemphasized apocalyptic futures can be used to support despotism and rashness. For example, catastrophic and ultimately inaccurate overpopulation scenarios in the 1960s and 1970s contributed to several countries adopting forced sterilization and abortion programs, including China’s one-child policy, which caused up to 100 million coerced abortions (7), disproportionately of girls. Past and present fascist and neofascist movements frequently use fears of environmental catastrophe to promote eugenics and oppose immigration and aid (8). The Sri Lankan government, concerned about pollution, rashly banned synthetic fertilizers and pesticides in 2021, contributing to an agricultural and economic crisis (9).”

In fact, militant naive extremism—in the form of communism—may be the single deadliest force in human history. For example, Chairman Mao’s Great Leap Forward was aimed at reducing class inequality and catching up to Britain’s industrial power. Who could be against that? And yet, it became a campaign of tragically naive policies and brutal repression that caused tens of millions of Chinese citizens to starve. The Soviet Union was similarly awful. I sometimes worry that we environmentalist flirt with glorifying messages (‘we just need to abandon capitalism!’), idols, and black-and-white tribalist frames (‘it’s all billionaires’, white men’s, and fossil-fuel companies’ fault!’) that are cozier with communist-like ideology than we realize. Would we accept an environmentalism similarly cozy with Nazi ideology? I doubt it (and I certainly would hope we wouldn’t).

How might militant naive idealism go awry in the future climate movement? Well, maybe, analogous to Sri Lanka’s fertilizer ban, someone will try to ban coal before it stops being a majority of many countries’ (including China’s) primary energy. Or maybe someone will rise to power who thinks that democracy is an obstacle to climate action and so democracy should be abandoned.

If we’re really going to transition our energy system, food system, infrastructure, and economy off of fossil fuels—and we need to!—we need to get the details right, to ensure that no one is left behind and to ensure that our tremendous societal progress of the past two centuries is not sacrificed along the way. So, we need to teach our students to appreciate our progress, and pay attention to the details. As I say to my students: these are serious issues, so you need to take them seriously.

Parting thoughts

Wherever you are on the political spectrum, there are lots of good reasons to reach across the aisle to people who think differently from you, and work together on solutions to climate change—the challenge of our time.

If you made it this far, thanks for reading/listening! Comments welcome.

While I deeply want to agree with this, I'm hung up on the fact that it seems like most scientists (ranging from environmental scientists, ecologists, and climate scientists) say we're already locked into civilizational collapse and possibly human extinction unless we decarbonize essentially overnight, and as such there's no time for this sort of consensus-building. Is there good evidence that these risks are not true, and we do have time to work through democratic processes? Is there any chance that the worst-case scenario under any circumstances falls short of total collapse/extinction, and is "just" so bad that we need to work hard to avoid it?