Economic development is key to addressing climate change

Development-driven adaptation is driving the bus on many, if not most, climate-sensitive outcomes. A summary of our new working paper.

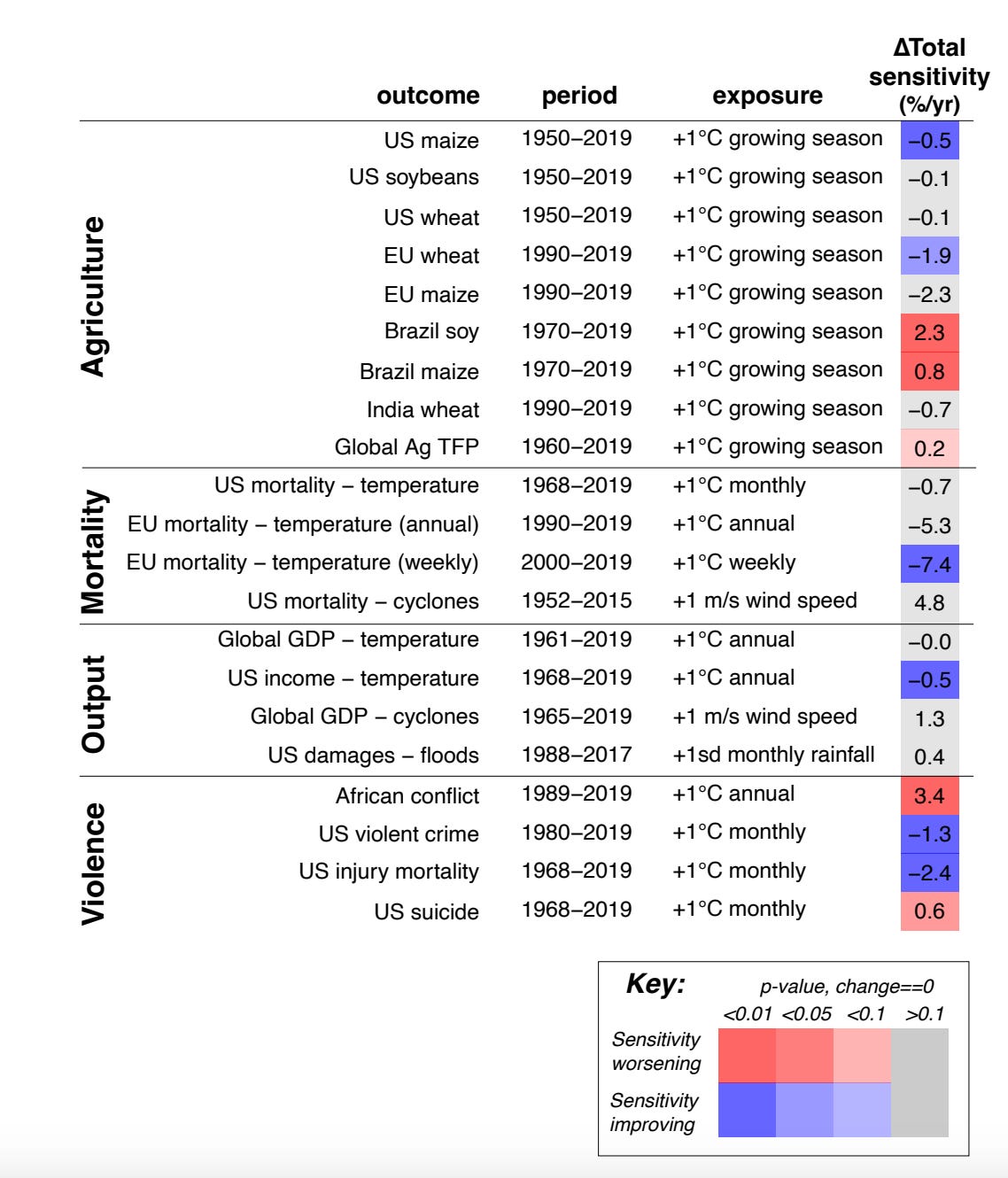

A bunch of heavy hitters in my field (environmental economics) published a sobering and widely discussed working paper in 2024 called “Are we adapting to climate change?” The paper estimated the sensitivities of a bunch of climate-sensitive outcomes to climate over several time periods, and found that most sensitivities were not decreasing (see below).

For example, the sensitivity of Brazilian soy and maize yields had actually gone up, by their estimate, meaning that a 1-degree increase in temperature was corresponding to a greater yield loss in recent years than it did 50 years ago. From these types of results (see below), they concluded (in their abstract) “the net effects of existing actions have largely not been successful in meaningfully reducing climate impacts in aggregate”.

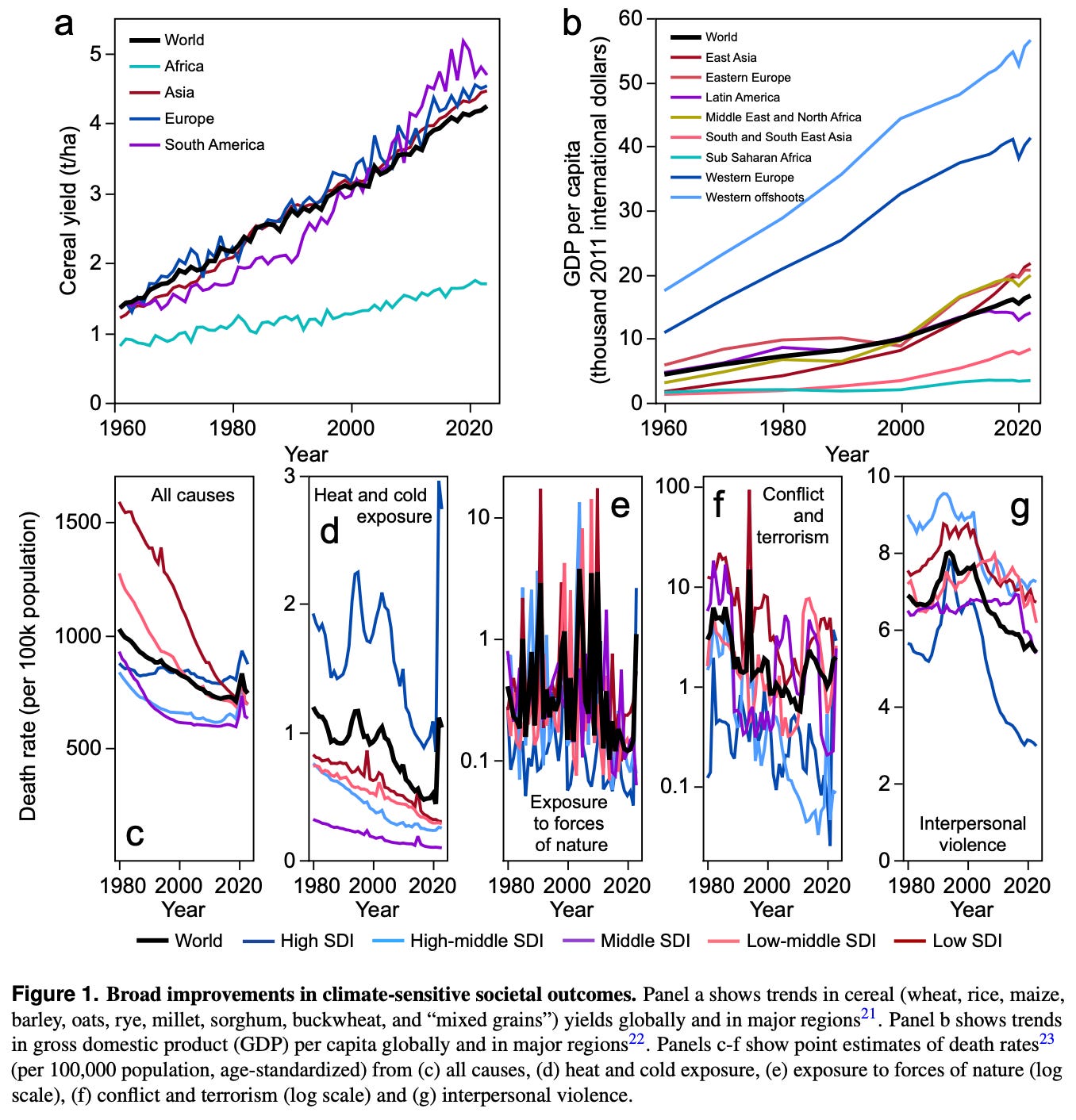

However, if you zoom out and just look at the overall time trends in the climate-sensitive outcomes Burke et al. examined—crop yields, economic output, violence and mortality—the trends are broadly and unmistakably improving almost everywhere (the 2022 EU heat wave notwithstanding) over the past several decades (see below). Brazilian cereal yields, for example? They have more than tripled over the past 50 years, despite their potentially worsening sensitivity to climate. Several books have been written about how the world is broadly getting better by measures that matter to human well-being, climate-sensitive and not.

So, are we adapting or not?

How do we wrap our heads around these apparently contradictory patterns? My colleagues—Patrick Brown, Matt Kahn and Roger Pielke Jr.—and I took on this question in a new working paper that we just released.

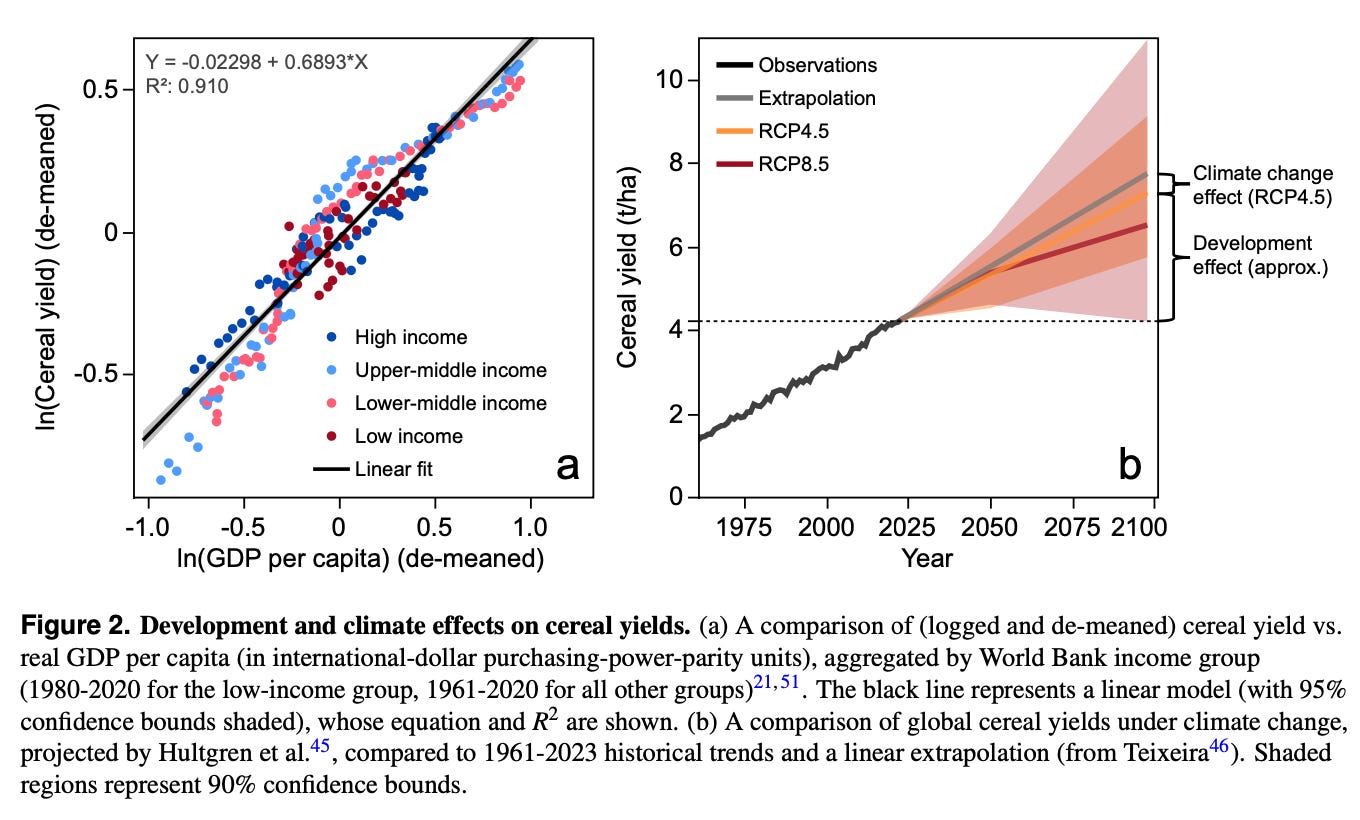

Our answer: if you decompose time trends in a climate-sensitive outcome in terms of the climate effect (sensitivity to climate x rate of climate change), the development effect (sensitivity to affluence x per capita economic growth rate), and everything else, you tend to find that the development effect dominates—often by an order of magnitude or more. We illustrated this numerically for global cereal crop yields, based on an excellent earlier analysis by Lauren Teixeira of the Breakthrough Institute and a widely discussed Nature paper by Andrew Hultgren et al. (see below).

In other words, even if an outcome’s (e.g., of crop yields’) climate sensitivity is worsening or not improving, increasing affluence is improving the outcome itself faster.

This suggests that development (and development-driven adaptation) are very important to improving climate-sensitive outcomes in the face of climate change. Research and policy discussions of adaptation often overlook the indirect benefits of development and focus on the (often much smaller) direct effects of intentional adaptation efforts (which are important too).

As we discuss in the paper, adaptation of all kinds is often an afterthought in climate change research, policy and public discourse. This needs to change.

Some implications of development driving the bus on climate-sensitive societal outcomes

The fact that economic development is often the dominant proximate driver of climate-sensitive outcomes, on policy-relevant timescales, has several important implications:

Economically harmful climate policies could have negative effects on climate-sensitive outcomes, not just the economy. For example, if your crop yields are being harmed by climate change, and you screw up your economy trying to drastically reduce your emissions, you might find your crop yields going down, not up. (The government of Sri Lanka ran an unfortunate experiment not too different from this a few years ago and the results were disastrous.)

We need to be cautious about how we interpret the social cost of carbon (SCC) in policy. The SCC measures the negative externality from carbon emissions via climate change. If there were no other externalities from carbon-emitting activities, then it would be societally optimal to have a carbon tax equal to the SCC, and to use the SCC in cost-benefit analyses (as the Obama, Biden, and Trump 45 administrations did). But most carbon emissions come from resource uses that are the base of the economy—things like energy and food—and cheap energy and food very likely has large positive externalities. So, blindly applying the SCC as a carbon tax could be devastating. For example, the Biden administration’s 190 USD/t SCC, as a carbon tax (which the Biden administration didn’t impose, to be clear), would more than double the price of oil and more than quadruple the price of coal. Would drastically hiking global energy prices—which would almost certainly cause a major economic disruption, disproportionately affecting the poor—really improve human well-being? If you think the answer might be ‘no’ (as I do), then you should interpret the SCC cautiously in policymaking.

No-climate counterfactuals in climate impacts research don’t make sense. It’s common for studies to estimate the effects of climate change on an outcome like crop yields, and then project that outcome forward with and without climate change—all else equal (implicitly or explicitly including economic development)—and express the difference as the projected effect of climate change on the outcome. But, if economic development is a key driver of both crop yields and climate change (via GHG emissions), how does it make sense to hold development equal, while varying climate change? Journalists need to be more cautious about how they interpret and report on this type of study. (E.g., no, climate change is not going to take away your breakfast.)

Economic development is a climate justice imperative, not a hindrance to climate justice, as a few scholars have sometimes argued. This was one of the central points of Bill Gates’ fall climate change memo that was maligned by many climate scientists and advocates. As our analysis shows, he was basically right.

Commons problems vs. races to the top

Economic development and adaptation have the sociopolitical advantages of having costs and benefits roughly matched in space and time. Economically beneficial GHG emissions reduction (mitigation) efforts, such as deploying cheap renewables and increasing efficiency, have similar advantages. In fact, because we can export new technologies to other countries, countries should have incentives to ‘race to the top’, chasing leadership in innovation and turning the commons problem on its head.

In contrast, economically costly mitigation efforts (even if they might be beneficial in the long run) face the classic commons problem, whereby their costs are local in space and time, and their benefits are diffuse.

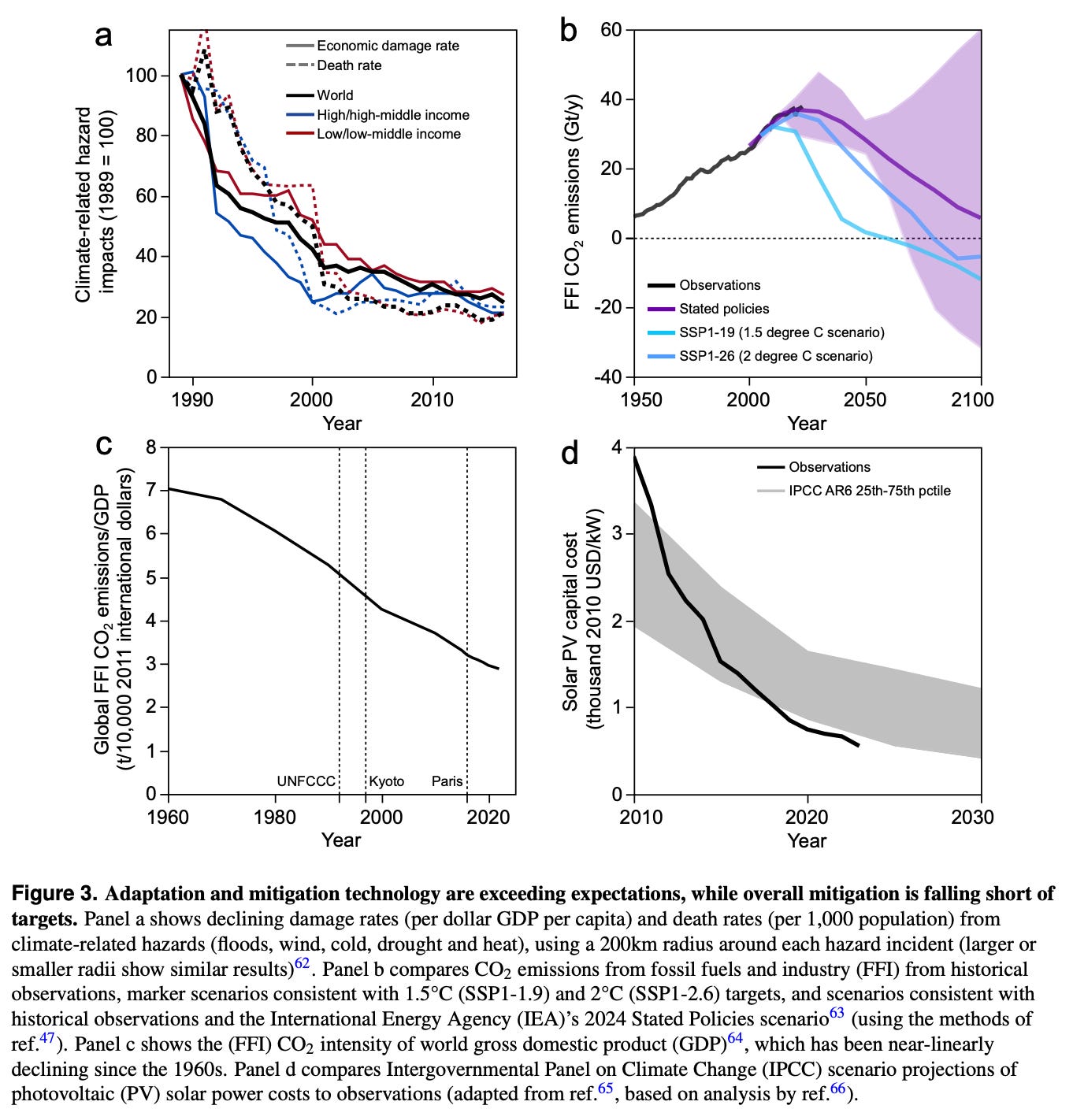

Perhaps for this reason, we see adaptation and economically beneficial mitigation often beating expectations, and the opposite for meeting emissions targets and bending the overall carbon intensity curve (see examples below).

Mitigation and adaptation both matter, but they protect us on different space and time scales.

Does this all mean mitigation doesn't matter? No. Emissions matter. The Earth keeps getting warmer until society reaches net zero GHG emissions, and the world should continue to work together to reduce them.

Governments are right to be cautious about climate policies that could be economically damaging, we argue, but they should be full-steam ahead on developing and deploying economically beneficial mitigation solutions (cheap renewables, efficiency improvements, EVs, etc.). They should also make big R&D investments to find more beneficial solutions. Otherwise, they risk allowing their countries to fall behind in the global clean tech race, not to mention leaving near-term economic benefits on the table.

But our analysis does imply that mitigation and adaptation/development protect us from climate change on different time and space scales. Adaptation doesn't reduce our chance of hitting a climate tipping point this century. Reducing emissions in Texas or California does approximately nothing for the climate—and therefore the floods, storms, fires, etc.—that we have to face next year.

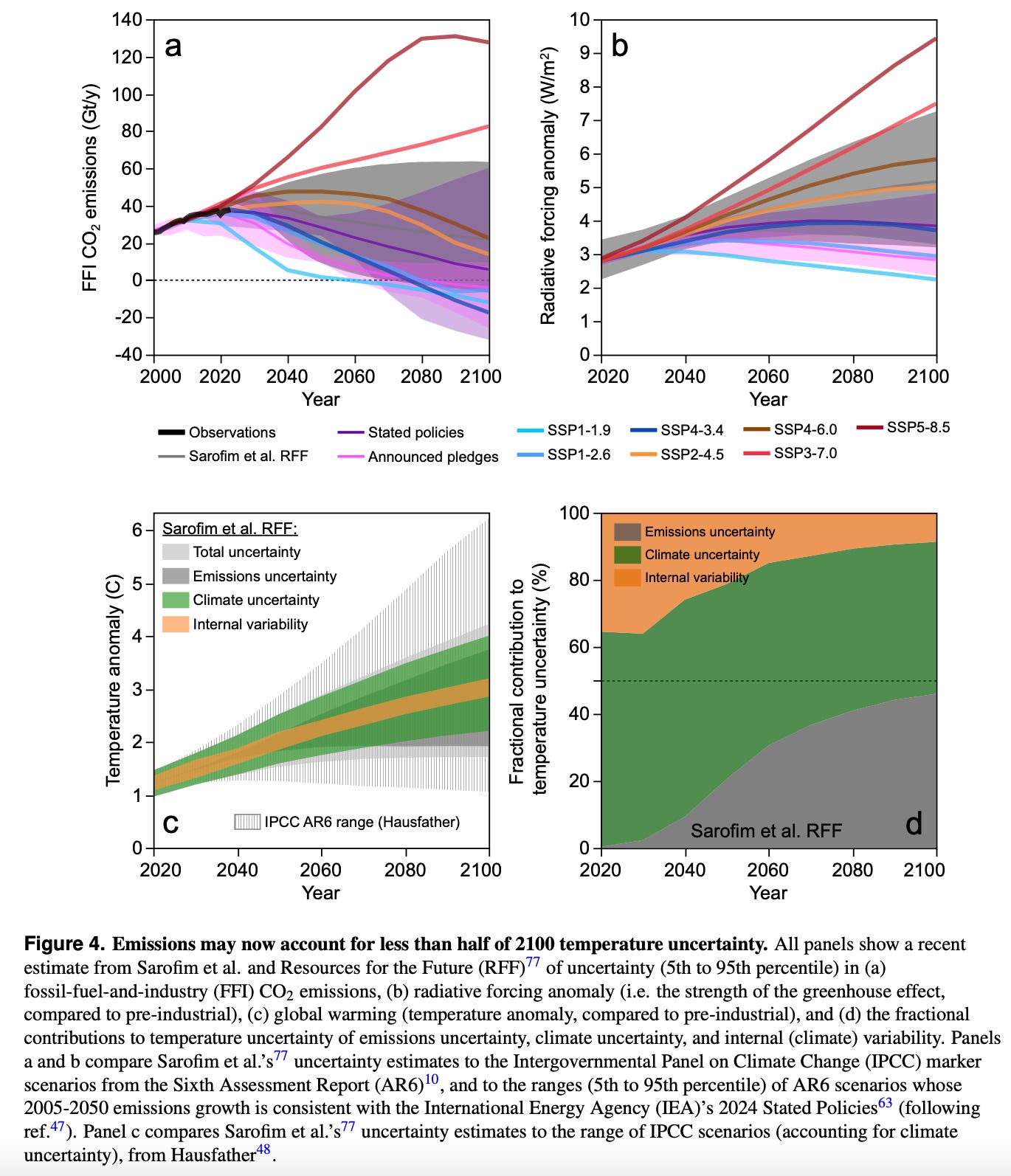

In fact, if you consider that the range of plausible emissions scenarios is narrowing, emissions uncertainty might now account for less than half of temperature uncertainty for the rest of this century, we argue.

Our climates are also going to be warmer for the rest of the century than they are today, even under the most ambitious mitigation scenarios (see panel c above). So there is no good reason to put off adapting, regardless of what our preferred mitigation approach is.

The ‘stopping smoking cures cancer’ fallacy

One of the things that inspired us to write this paper was statements from advocates, public intellectuals (like Bill Nye last summer), and occasionally even climate scientists, that sound like: "if we don't want more fires/floods, we need to get off of fossil fuels". These types of statements are unhelpful and misleading. They commit what I call the "stopping smoking cures cancer" fallacy.

Emissions via climate change affect risks of some extreme events (just like smoking causes cancer), but stopping emissions (especially locally) does not protect you from tomorrow’s extreme events (just like you need cancer treatment if you have cancer).

If we want less impact from floods, fires, storms, etc., next year (or even over the coming decades) we need to build better infrastructure, warning systems, etc. Growing our economies will naturally help with some of these things. Mitigation ultimately matters too, but it operates at much larger space and time scales.

For example, we show in the paper that Louisiana could have eliminated their GHG emissions after Hurricane Katrina (which would have devastated their economy) and done virtually nothing to reduce their near-term hurricane risk. In contrast, they were able to improve their resilience from improving their levies and warning systems, which lessened the impact of Hurricane Ida in 2021.

In sum, our paper argues that we need to pay a lot more attention to adaptation and development in efforts to address climate change. But mitigation still matters, and the world should keep working towards bending the curve, especially in areas (which are plentiful) that have immediate economic co-benefits.