Don't over-interpret the 'red wave' and 'no climate voters' election stories

On the 'red wave', look at the Senate map. On climate, look more closely at the polls.

As people have discussed ad nauseam already since last Tuesday’s election: it was a good night for Donald Trump and the Republicans, who won the White House and (probably) both chambers of Congress (the House hasn’t officially been called yet, as of this writing). It was also not a good night for people who want an aggressive approach to reducing U.S. greenhouse gas emissions (to address climate change) to be a priority for the next administration.

Some people have taken the second point about climate change further during this election cycle (before and after election day) to say things like: “the notion that there are climate voters (didn’t work)” and “climate is the problem”. (I intentionally chose these examples, from two of my favorite public intellectuals whom I deeply respect and whose work you all should follow, to illustrate that smart people believe these things.)

I don’t want to dismiss these narratives entirely. Both have important grains of truth to them. But I also think both narratives risk being over-interpreted by both sides.

Senate results complicate the ‘red wave’ story

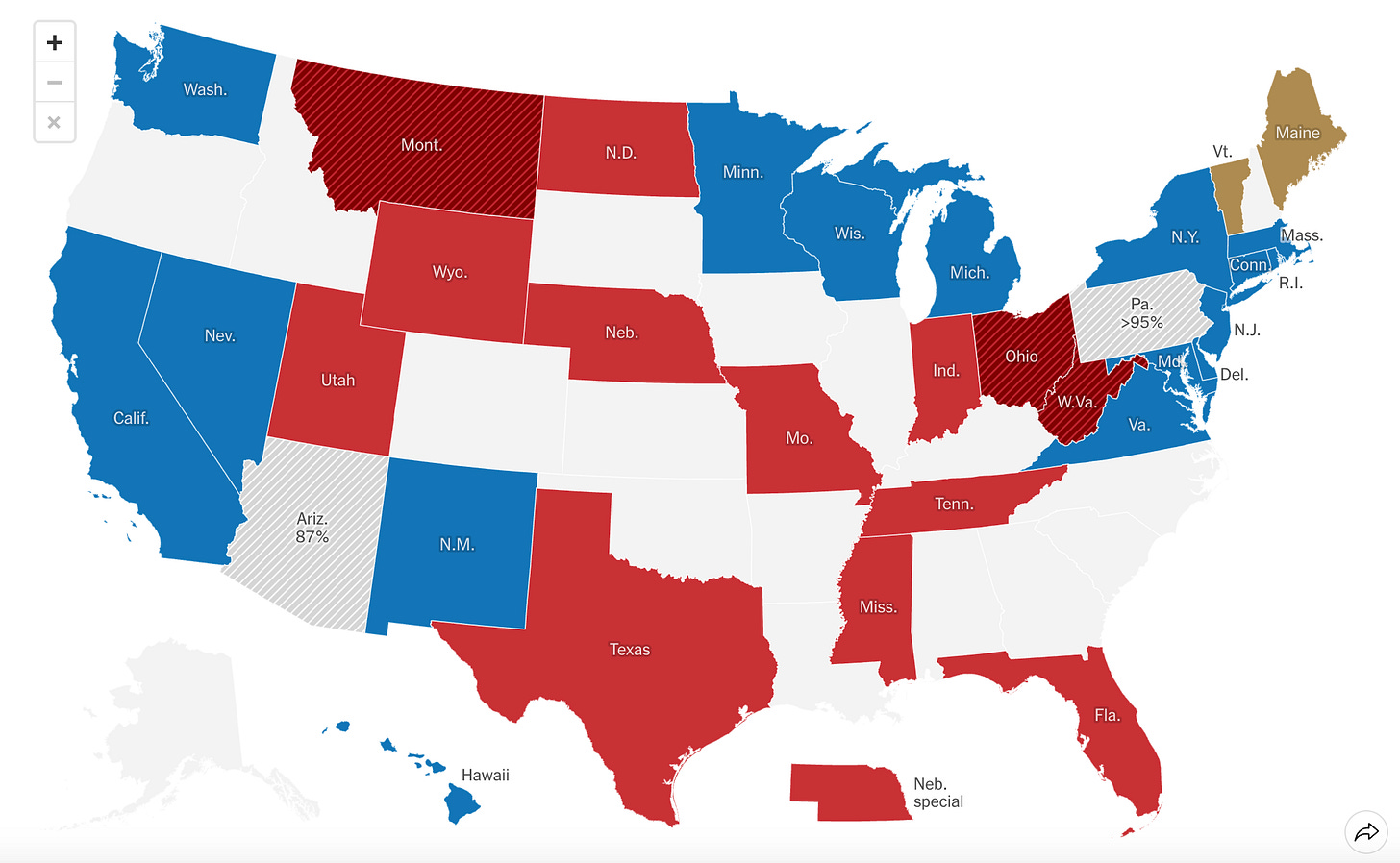

By the time all the votes are counted, it seems like Democrats will end up winning at least four out of five Senate races in swing states. They have won Michigan, Wisconsin, Nevada, and probably Arizona (the New York Times hasn’t called the race yet, as of this writing, but some other outlets have). Pennsylvania is currently too close to call, with the Republican Dave McCormick leading by less than half a point. It’s possible that Bob Casey will come back and the Democrats will end up sweeping the swing states in the Senate. (Update: McCormick won, but the larger point still stands.)

So, the Democrats are losing the Senate because it’s a bad map for them this year. They lost seats in deep-red West Virginia (with Joe Manchin retiring) and Montana (with John Tester narrowly losing), and lately quite-red Ohio (with Sherrod Brown narrowly losing). The Democrats probably would have lost the Senate this year no matter what. (And three of the winning Democratic Senate candidates in swing states Trump won—Jacky Rosen (NV), Tammy Baldwin (WI), and Elissa Slotkin (MI)—were women running against men, which somewhat undercuts the idea that Harris lost because of her gender.) Although it looks like the Democrats will probably lose the House too, it is so close that it still hasn't been called, and only three seats (out of 435) have been called as D-to-R flips so far.

The point is: Trump had a good night and/or Harris had a bad night. But below the top of the ticket, the election overall does not seem like the sweeping rebuke of the Democrats or the big red wave that many are making it out to be.

Why was it such a bad night for Harris? I cover this more in a post scheduled for Tuesday morning, but briefly:

Inflation seems to have played a big role, like it did against incumbents all over the world. See this excellent Financial Times piece by John Burn-Murdoch. Harris did not succeed (and was not given enough time, given Biden’s late exit) in distancing herself from Biden’s unpopularity as the incumbent. When given the explicit opportunity to do so (e.g., on The View), she didn’t take it.

The public being fed up with ‘woke’ faculty-lounge identity politics and bad Democratic local governance seems to have played a role, too. Josh Barro outlines the effects of the governance issues here. This paper by Rachel Wetts and Robb Willer shows that disliking woke identity politics is the single best predictor among white people of supporting Trump recently (more than class, racial prejudice, or even ideology). This collection of polls by Kevin Drum shows how unpopular progressive positions are on most cultural issues (besides abortion and guns), with their biggest deficit being on the Israel issue that was in the news a lot this past year, with a lot of negative coverage of the sometimes-antisemitic campus protests. Progressives lost several local races (e.g. for San Francisco Mayor, Los Angeles District Attorney, and several ballot measures). So, Harris' unpopular 2020 positions probably cost her too. Although she changed most of them, she didn’t clearly articulate why she changed them, instead offering platitudes like “My values have not changed”.

Harris ran a bad campaign in several other important ways. Although she ran on patriotism and positivity, and she did not run on her gender (all smart strategies), she shunned unscripted interviews for too long, avoided key podcasts like Joe Rogan’s, did not distance herself from Biden or the months-long cover-up of his cognitive issues before he dropped out of the race, her unpopular 2020 stances, etc. Her campaign alienated young men, and seems to have been punished for it by both them and their Gen-X mothers.

All this to say, Kamala Harris (and the progressive wing down ballot) losing the election seems to be the main takeaway for me. Donald Trump deserves credit for running an effective campaign and for making an unprecedented political comeback. But, if you consider that his net-unfavorable rating has barely changed for years (including before and after this election), Harris losing seems more convincing to me than Trump winning, as an explanation for the popular vote. And the Democrats did not lose as big down ballot as people seem to think.

So, other than the rebuke of faculty-lounge identity politics, immigration, and soft-on-crime policies (which seems real to me), I don’t see evidence in this election alone that we are headed for some type of conservative decade, or that the Democrats were crushed as a party. If Trump starts separating children from their parents at the border, allows his colleagues to ban abortion, or lets RFK Jr. undermine vaccines or pursue dangerous Sri-Lanka-like agricultural policies, my guess is that the Republicans will get destroyed in the 2026 and 2028 elections.

Democrats should reckon with their loss, but do so with measure. Republicans should enjoy their mandate, but do so with humility.

Most Americans do care about climate change, and climate change probably did help Harris more than Trump

The story that loud and extreme rhetoric on climate change from some progressives—including Harris in the 2020 primary and Biden occasionally on the stump—is unpopular, and therefore might have hurt Harris in the election, seems plausible. It’s also true that neither party talked about climate change much during the campaign, and relatively few voters rate it as their top issue. Finally, it’s true that some popular progressive climate ideas, like phasing out fossil fuels (or banning fracking or natural gas exports) are unpopular.

But, if your take is that climate change overall hurt the Democrats in this election, or that there were no climate-motivated voters, I say: hang on just a second and look more closely at the polls.

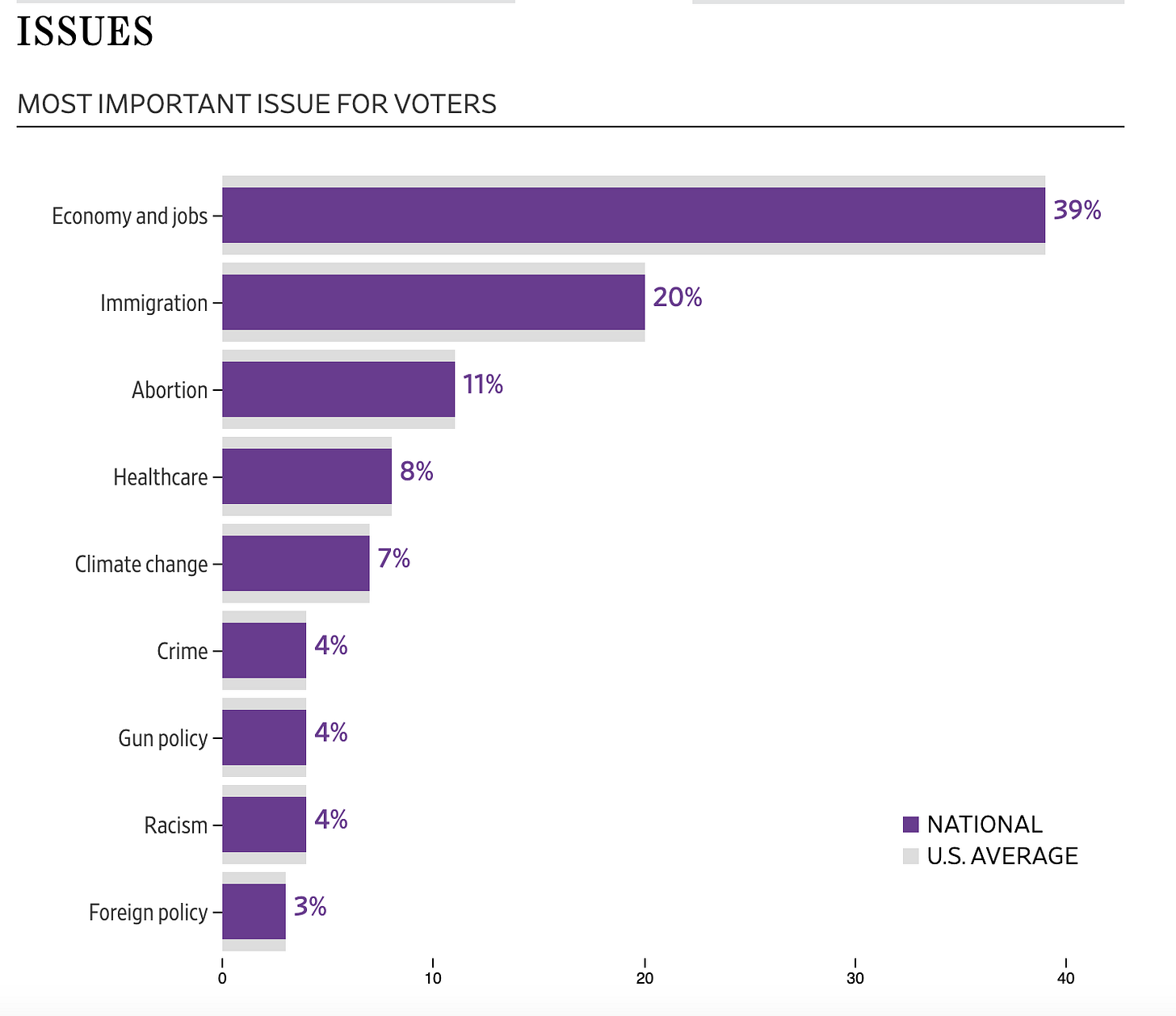

For example, a post-election Associated Press exit poll from 120,000 voters found that more voters rated climate change as their top issue in this election than crime or foreign policy.

A late-August Quinnipiac poll found that voters preferred Harris over Trump on climate change by 25 points—the largest margin either candidate enjoyed on any issue by far.

Polls throughout this election cycle have found a two-or-three-to-one preference among U.S. voters for candidates who support action on climate change (e.g., see below).

The Yale Climate Opinion Maps survey project suggests that, if “Should the President/Congress do more to address global warming?” was the key ballot question, the “Yes” side (closer to Harris’ position than Trump’s, historically) would have won the popular vote and both houses of Congress in a landslide.

Lastly, despite Biden’s occasionally hyperbolic rhetoric on climate change, he mostly governed from the center on the issue during his term. He pursued an all-of-the-above approach (i.e. supporting both clean technologies and oil and gas) that is popular and, as a result, is likely to be maintained (for the most part) by the Trump administration and the next Congress (see my earlier post on this).

All this considered, it seems much more likely to me that climate change was net-positive as an issue for Harris than it was for Trump. My research group estimated that it was similarly a net positive for Biden in 2020 and Clinton in 2016 (both also running against Trump), and may have made a big enough difference to tip the 2020 election to Biden, given how close it was (though it is hard to measure the magnitude of the effect precisely, as we discuss).

As someone who thinks climate change can only be addressed by a bipartisan approach, I would be thrilled to live in a world where climate change didn’t always help the Democrats in elections. But I don’t think we live in that world yet.

Why, then, didn’t Harris run more on climate change? My best guess (similar to others) is it’s a combination of three factors.

She didn’t see a political opportunity for an additional big-spending bill beyond those already passed during the Biden administration, given public concerns about inflation and the national debt, and the near-certainty that the Republicans would control the Senate, even if she won (see above). So, why make new promises you can’t deliver on, when the people who would most want new climate promises are largely already in your base?

She felt (accurately) that she needed to distance herself from her unpopular and sometimes-extreme stances from the 2020 campaign, which included unpopular climate stances (on fracking and the Green New Deal, for example).

There were other issues occupying the public consciousness (like the economy, immigration, and abortion; see the chart above) that she preferred to focus on.

I suspect Trump didn’t talk much about climate change because his base mostly doesn’t rank it as a top-priority issue, and because his past stances have been unpopular with independents and young and moderate Republicans, and consequently they were potentially costly in previous elections. With politically favorable messages to run on regarding immigration and the economy, Trump didn’t need to talk about climate.

So, my political advice to the Trump administration and Republicans in Congress is to keep governing in the center on climate change, like the Biden administration did. And my political advice to the Democrats is to tone down the hyperbolic rhetoric (‘it’s the end of the world’, ‘it’s a crisis’, ‘it’s a catastrophe’, ‘it’s more dangerous than nuclear war’, etc.) and stick to the facts; distance your climate approach from unpopular woke, anti-growth, or anti-American policies or rhetoric; support energy security and cheap, reliable energy as goals and help innovators and markets clean up the mix of that cheap, reliable energy; but, at the same time, don’t shy away from saying that climate change is real and important, and needs to be a priority for the country.