U.S. progress on climate change will continue under the second Trump administration, despite the vibe shift

Expect a big change in rhetoric, some change in policy, but little change in the path of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions.

Although climate change was not a top voting or campaign issue in this election, it is an issue that most Americans are worried about and want the government to take seriously. With Donald J. Trump set to return to the White House in January, some climate scientists and advocates are worried about what Trump’s election might mean for climate policy and climate progress in the United States and globally.

The simple answer is that no one knows. But, I think we have enough information to make an educated guess. Compared to the Biden-Harris administration, I expect to see a major change in the next Trump administration’s rhetoric and some change in its policy.

But I expect little change in the decline rate of American greenhouse gas emissions. U.S. emissions have been declining at a steady linear rate for the past three presidential administrations, including Trump’s first term. Many key drivers of emissions decline are beyond the reach of federal policy. And the most important federal policies to our current progress have broader support than many people realize, including among Republicans in Congress. They would need acts of Congress to be repealed, which I doubt will happen.

Expect different approaches and rhetoric

The next Trump administration will undoubtedly have a different approach and rhetoric on climate change than the Biden-Harris administration. For example, Trump has called climate change a “hoax” and climate policies a “scam”, and he repeatedly promised to “drill, baby, drill” (for oil and gas) during this year’s campaign. In contrast, Biden has called climate change a “crisis” and a greater threat than nuclear war. (For the record, I think both of these sets of rhetoric are too extreme.)

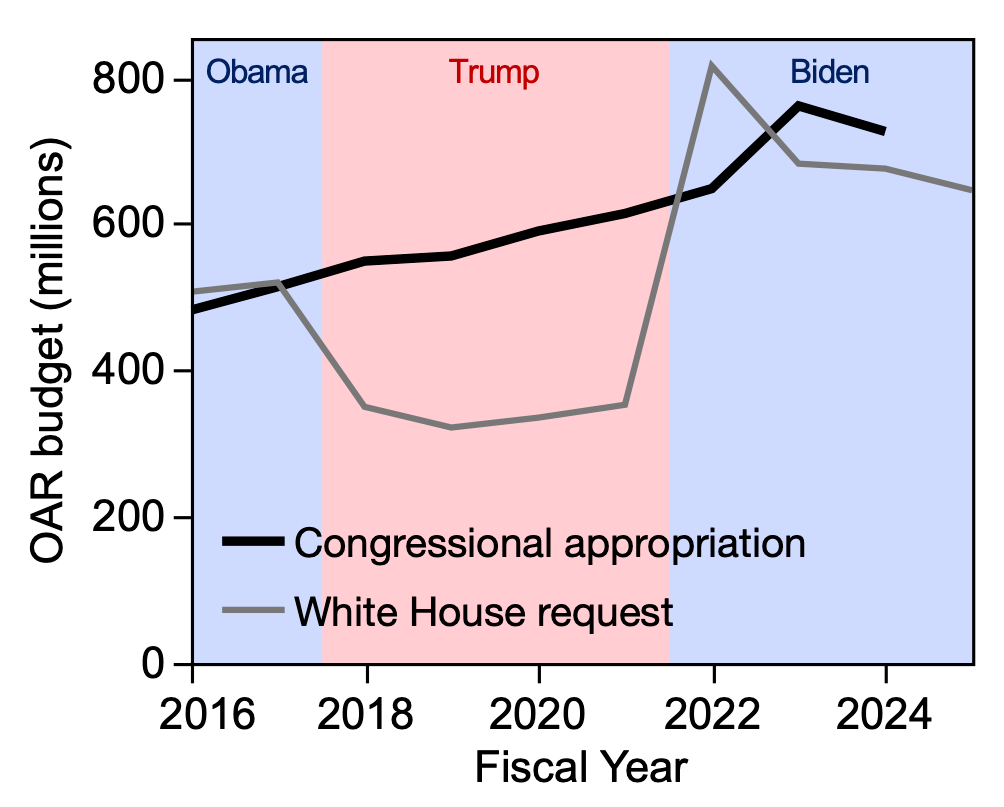

During Trump’s previous term in office, he withdrew the U.S. from the Paris Agreement and he rolled back 125 environmental regulations. Several of his White House budget requests proposed significant cuts to federal climate science funding, but Congress ultimately maintained or increased the funding each year he was in office, and it passed significant increases in science funding as a whole. Environmental non-profit organizations saw significant increases in private donations.

The Biden administration passed several major climate laws, including the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), and the CHIPS and Science Act. These laws are advancing the low-carbon economy primarily through subsidies, tax credits, research and development (R&D) spending, and industrial policy. The IRA passed Congress on party lines, while the other two laws were bipartisan. The administration also passed some smaller laws, like the bipartisan Growing Climate Solutions Act (helping farmers and forest landowners access carbon markets for nature-based solutions), and several regulations, including a recent pause on LNG export permits (which was halted by a federal judge) and national standards for vehicle emissions.

Trump has signaled that he plans to cut regulations, expand oil and gas drilling, and rescind unspent funds under the IRA. The Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025 policy blueprint calls for significant cuts to federal environmental regulations and federal climate science funding. Trump did not endorse Project 2025 during the campaign, and he has made no indication that he will endorse it since winning the election. But it was put together by many of his former staffers and was intended as a blueprint for his next term.

Expect similar declines in emissions, and increases in oil and gas production

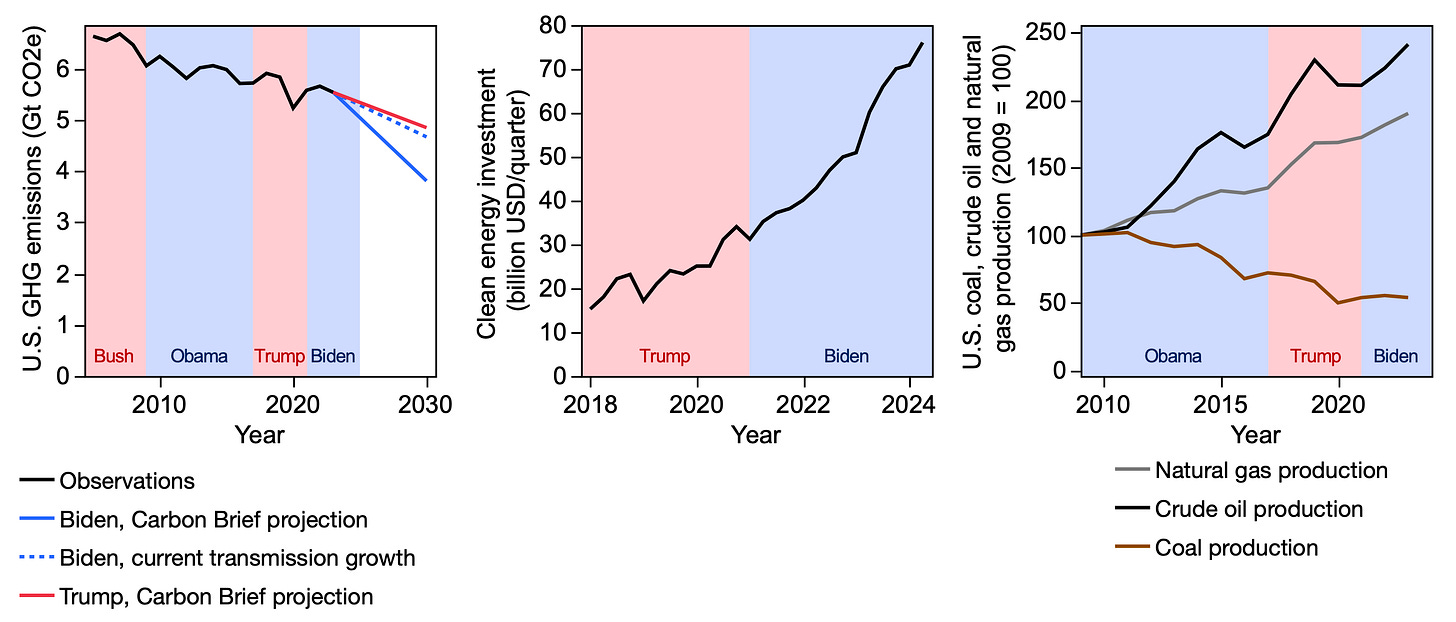

Despite all these differences in policy and rhetoric, U.S. greenhouse gas emissions have decreased linearly, on average, at a consistent rate of roughly 1% per year, over the past three presidential administrations, which includes Trump’s first term (left panel in the chart below). I expect that this pattern will hold steady during the second Trump administration.

To illustrate this prediction more specifically, consider a recent Carbon Brief analysis, which compared future emissions projections under “Biden” policies (assuming stylized uptake and implementation success) and a “Trump” scenario in which these policies are completely eliminated. Carbon Brief projects a roughly 20% difference in 2030 emissions between these two scenarios, with emissions declining in both cases.

However, I calculate that this difference shrinks to 5% if we assume that the U.S. cannot increase the rate at which electricity transmission lines are built, based on an earlier Princeton University REPEAT Project analysis (left panel in the chart above). If we relax other stylized assumptions in the “Biden” model, or we assume that Trump does not eliminate all of Biden’s climate policies (which I argue below is likely), the difference in 2030 emissions would become even smaller—likely in the ballpark of a continuing the 1% per year reduction in emissions (see the chart), or perhaps slightly faster emissions reductions if technology continues to improve, and if progress is made on permitting reform, to speed up transmission and utility-scale renewable energy construction. There is a bipartisan permitting reform bill in Congress currently, which does this (and also speeds up permitting for oil and gas), which I would expect the Trump administration to support.

U.S. greenhouse gas emissions have been decreasing over the past two decades for three main reasons: coal production decreased; energy efficiency improved throughout the economy; and renewable energy production increased, especially in the electricity sector. U.S. oil and gas production has also increased throughout this period, spanning the Obama, Trump, and Biden administrations (right panel in the chart above). In fact, the U.S. recently became the biggest crude oil producer in world history, under the Biden administration.

In other words, the U.S. is gradually decreasing its greenhouse gas emissions, while increasing its energy production, using an all-of-the-above (except for coal) approach. I expect these trends will continue during the Trump administration, because most of their drivers are outside of the White House, and because an all-of-the-above approach is popular.

Key drivers are outside the White House

The main drivers of recent U.S. energy and greenhouse gas emission trends exist outside the federal government—in the private sector and at the state and local levels. Renewable energy is cost competitive. Global and U.S. markets are sending clear long-term signals favoring renewables and other low-carbon technologies. Global, state and local markets—fueled by geopolitical instability in Russia and the Middle East—are also sending clear short-to-medium-term market signals favoring U.S. oil and natural gas.

As a result of these market signals, the private sector is leading the energy transition now in many parts of the United States. An audit led by my former student Grace Kroeger found that electric utilities have more ambitious decarbonization targets than state governments, on average. Several Republican-controlled states like Texas and Oklahoma, with few climate policies, are leading the country in renewable energy production, driven by private investments. Nationally, clean energy investments skyrocketed during both the Trump and Biden administrations (center panel in the chart above).

Some large Democrat-controlled states, like California, New York and Colorado, have ambitious state-level mandates for decarbonizing their electricity sectors. California plans to require all new vehicles sold to be zero emissions by 2035. These policies send market signals to electricity and vehicle suppliers across the country, regardless of who is in the White House. As the technology improves, consumers will increasingly demand cleaner and safer renewable energy (and nuclear). Once the technology and availability of charging stations improves to the point where people don’t worry about range and charging time, consumers will increasingly demand electric vehicles too, which are cleaner, quieter, and have better acceleration.

Investors in utility-scale projects are typically making decisions on time scales of decades, not single presidential cycles. That makes it hard for a single administration to move investment against the grain of the long-term market trends, even if they try. For example, Trump promised to reverse the decline of American coal during his last term, and he failed (see the chart above). He would similarly fail to stop renewable energy growth, or bring back coal, this time if he tried (and I don’t think he will try).

All of the above will persist because it is popular

The second reason I suspect America’s current all-of-the-above approach to climate and energy will survive in the Trump administration is that it is popular across party lines. Renewable energy is popular (more so than fossil fuels in some polls), and ignoring the climate issue is unpopular. But phasing out fossil fuels is also unpopular. For these reasons, the all-of-the-above approach has key allies on both sides of the aisle, including among Republicans in Congress and at state and local levels.

The major climate laws I mentioned above were passed with bipartisan support, with the exception of the IRA. One of the largest caucuses in the U.S. House of Representatives currently is the Conservative Climate Caucus, a group of nearly 100 Republican members who care about climate change and support an all-of-the-above approach to addressing it. That caucus’ founder and leader, John Curtis (R-UT), was just elected to the Senate, in the seat vacated by Mitt Romney. He will be a key vote in the GOP’s narrow Senate majority. The caucus members remaining in the House will be key to the GOP’s razor-thin majority in that chamber (if they even get one, which has not yet been called as of this writing).

At the state level, my former student Renae Marshall and I found over 100 decarbonization bills (i.e. bills that help the energy transition in some way) passed between 2015 and 2020 by Republican-controlled governments. We also found many bipartisan bills passed in Democrat-controlled states. Bipartisan and Republican-backed bills tended to expand choice rather than restricting choice (e.g. subsidies and market-access expansions rather than restrictions), use financial incentives supporting clean energy, and frame efforts to address inequality in terms of class rather than race. (A later paper led by Marshall found that pairing climate policies with race- and gender-conscious social justice policies turns off moderate and conservative voters, too.)

Interestingly, these characteristics of Republican-supported state-level bills (mostly) describe the climate-change aspects of the IRA. (The IRA also had unrelated elements concerning taxes and prescription drugs.) So, the Biden administration (helped by moderate Senator Joe Manchin) may have gotten the message about which climate policies can achieve broad support and which ones cannot.

The IRA and other Biden administration industrial policies have also helped spur a boom in private manufacturing investment not seen in decades (see the chart below). The policies emphasize re-shoring protecting and prioritizing U.S. domestic industries. Most of the money from the IRA is going to Republican-led Congressional districts, creating jobs in rural areas, some of which have been left behind by de-industrialization. For these reasons, many analysts expect resistance from some Congressional Republicans to any attempt by the Trump administration to roll back the IRA’s clean energy subsidies on a large scale. Republican House Speaker Mike Johnson recently called for revising the IRA “with a scalpel and not a sledgehammer”.

All told, my best guess is therefore that the key provisions of the IRA (and the IIJA and CHIPS Act) will survive Trump’s second term. I think Obamacare (the Affordable care Act) is a good analogy here. One could sell a negative story about it—its cost, the individual mandate, effects on people’s private insurance, etc.—to win votes. But actually getting rid of it would mean taking health coverage away from millions of Americans, which would be very bad politics. Obamacare survived an attempt at repeal during Trump’s previous term, and Republicans seem to understand the bad politics of further attempts to repeal it now.

Similarly, you can tell a negative story about the IRA on the campaign trail—inflation was too high during Biden’s term (true); excessive government spending was to blame (partly true, regarding the American Rescue Plan of 2021, but 2020-2023 inflation mostly was caused by global pandemic-related factors); and the IRA spends a sizable amount of money (true, but much less than the American Rescue Plan, and inflation was already under control once the IRA money started going out the door). But the political reality of repealing a law (the IRA) that isn’t actually contributing much to inflation, and is actually creating jobs and driving investment into rural and Republican districts, is not as pretty.

Our Republican Governor here in Wyoming, Mark Gordon, is a fascinating case study in the winning politics of an all-of-the-above approach to climate and energy. Wyoming has one of the most fossil-fuel dependent economies of any state in the country. It is the single-most Trump-supporting state in the country. It has the least public support for climate policy of any state in the country. Yet, Governor Gordon explicitly supports an all-of-the-above approach, including renewables, nuclear, and carbon capture, as well as fossil fuels. He has publicly called climate change “urgent”. He is also one of the most popular Governors in the country, having the fourth-highest approval rating at 64% approval and 39% net-favorable.

Regulations, the Paris Agreement, foreign aid, and climate science under fire

I expect the Trump administration to push for significant reductions in regulations, foreign aid (including aid related to climate change) and federal climate science funding, and to remove the U.S. from some international climate agreements. My best guess is that he will succeed in cutting regulations and withdrawing the U.S. from some international climate agreements. But I expect that he will not succeed in significantly cutting foreign aid or climate science funding, because Congress controls the purse strings, and both foreign aid and science funding have historically enjoyed broad (albeit not total) bipartisan support. Indeed, during Trump’s previous term, he requested cuts to climate science funding and foreign aid, but Congress did not support his requests.

During is previous term, Trump cut over 100 environmental regulations. I expect more of the same this time. He will probably roll back Biden’s new vehicle-emission standards, for example. Any regulations Trump cuts may have effects on emissions, but my best guess is that the effects will be small, given the broader market tailwinds behind clean technologies and electric vehicles, and also given the fact that the previous regulation cuts did not significantly slow emissions progress during his last term (see the chart above). Some regulation cuts might also help to unleash clean energy and transmission projects, thereby accelerating emissions cuts.

Trump’s campaign promised to withdraw the U.S. from the Paris agreement again, and suggested that he may withdraw the U.S. from the entire United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). He withdrew the U.S. from the Paris Agreement during his first term and he tried to reduce federal foreign climate aid. My understanding is that these policy positions are linked to each other. Trump sees the funding obligations that rich countries have for climate adaptation and damages under international climate agreements as a rip off, and he sees foreign aid generally as contrary to his America First agenda. As outlined above, he was not successful in making major cuts to foreign aid last term, and it is not clear he will be successful this term either.

Despite Trump’s White House proposing cuts to federal science funding, including climate science, during his first term, Congress increased the funding (see below). My best guess is that the same thing will happen again. I expect federal science, including climate science, to retain support for the following reasons.

First, the number of jobs supported by federal science funding is probably in the millions, and it is spread out across the country. If we zoom in on major federal laboratories, centers, and cooperative institutes funded by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), most of which conduct climate-, weather-, and/or environment-related research (and which are targeted by Project 2025 for cuts), we see many in red states and swing states (e.g., Florida, Oklahoma, Alabama, Wisconsin, Mississippi), as well as blue states. (Disclaimer: I used to work for one of the cooperative institutes, CIRES, at the University of Colorado Boulder, before I moved to Wyoming). Are a majority of Senators and Members of Congress, in a situation with razor-thin partisan majorities in each chamber, really going to want to make draconian cuts to these programs and destroy well-paying jobs in their states? My guess is no.

Second, U.S. federal science, and federally-funded science, is the crown jewel of the global scientific enterprise, and it spawns countless commercializable innovations and economically valuable data. This is true on climate change and weather science, too. Our world leadership in science, and our ability to attract the best and brightest minds from all over the world (the South-African-Canadian Elon Musk being a notable example) is one of the main reasons America is the predominant global economic, military, and technological superpower that it is. Dismantling that leadership—at a time when it is being challenged by our main geopolitical rival, China—does not seem consistent with American greatness nor with America First. My guess is that many Republicans (and Democrats) will agree.

All that said, we scientists and academics need to get out of our own way, too. Conservatives in this country and others are not wrong to believe that America’s scientific and academic workforce is overwhelmingly composed of liberals and Democrats. They are also not wrong to notice that our scientific institutions sometimes step out of their lanes into inappropriate activist stances. I and many others have written about these problems before, and the need for scientific and academic institutions to become more non-partisan and politically diverse to address them (and improve our science while we’re at it).

However, there are big differences in the magnitude of this problem by scientific discipline and institution. Physical scientists (physicists, atmospheric scientists, geologists, chemists, etc.) have much more balanced politics than the social sciences (except for economics) and humanities. Federal scientists also have strict prohibitions on engaging in partisan activities. In my experience, probably for these reasons, federal physical climate scientists are some of the least partisan members of the climate change research community.

So, my advice to Republicans who want better, less partisan science (an objective I share) is: don’t punish the national labs because you’re upset with university sociology departments or the handful of private university professors who are especially loud, hyperbolic, and partisan on social media. And target politicizing policies and structures within scientific institutions (e.g., any diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programs that illegally compel political speech or promote illegal protected-class discrimination), rather than dismantling the scientific institutions themselves. Just like liberals should have pushed for better policing—not less policing—as a solution to police brutality, conservatives should push for better science—not less science—as a solution to the politicization of science.

The X-factor of Elon Musk (pun intended)

Elon Musk—a key Trump ally and donor in his 2024 campaign—is one of the world’s leading clean technology entrepreneurs, who believes in and cares about climate change. Some observers believe Musk could be a moderating force on climate change policy and rhetoric during the second Trump term. Musk’s Tesla stock soared following Trump’s election victory, and his association with Trump is believed to be a cause of Trump’s softening rhetoric on electric vehicles. Musk made the case for solar and nuclear power to Trump on an August public livestream. During the previous Trump administration, Musk resigned from an advisory group in protest of Trump’s decision to withdraw from the Paris Agreement. The idea that Musk would push back against hard-line anti-climate-science or anti-clean-technology policies seems like a good bet.

Don’t stop working on climate solutions

As with other posts in my ‘everything will probably be fine regardless of who the President is’ genre of late, my optimism should not be confused with a call for complacency.

If you care about climate change, keep working on it. If you think your representatives aren’t taking it seriously enough, let them know. Keep working on solutions to make the energy transition cheaper and its economic benefits more salient, and the politics of the energy transition will keep getting better too. If you think the government is leaving resources on the table, donate to an environmental non-profit (as many people did last time Trump was in office).

And keep building bridges across the aisle on this issue and others. There is no feasible way to address a society-wide issue like climate change without bipartisan cooperation and support. Thanks for coming to my TED(-style) talk.

As an addendum--underscoring the popularity of the current all-of-the-above climate policy--Exxon's CEO just urged the Trump administration to not roll back too much climate policy: https://www.politico.com/news/2024/11/12/exxon-ceo-us-climate-policy-00188927