Polarization will continue to destroy itself, no matter who wins the election today

It will happen faster if Harris wins, but it will happen either way.

A few months ago, I wrote a long essay called “How polarization will destroy itself”, which argued that polarization and the power of extremism on both sides probably peaked in 2020-2021, and that this trend will continue for the foreseeable future. As we reach the end of a hyper-polarizing election cycle—in which each side has accused the other of being fascist and a threat to the republic—I imagine my prediction seems naive and Pollyanaish to some. But I stand by it, no matter who wins the White House today.

Before I make my case, let me be clear: I am not arguing for ambivalence about this election. The candidates have extremely different governing styles, worldviews, and platforms. Both have been in the public eye for decades and have spent a term as sitting President (Trump) or Vice President (Harris). No matter where you reside on the political spectrum, you should have lots of information to go on. If you’re still undecided because you dislike both candidates, I encourage you to watch this substantive Free Press debate between Sam Harris and Ben Shapiro, who both dislike both candidates and yet strongly disagree on whom to vote for.

With that throat clearing out of the way, I will summarize evidence that polarization has peaked, and then describe why and how I think it will continue to decline in the long term, regardless of who wins the election. In short, it is mainly markets—for dollars, votes, and ideas—driving the current declines in polarization and the power of political extremes on both sides. The occupant of the White House does not have the power to stop these things in the long run, even if they wanted to.

Polarization is already decreasing

Here is a brief, approximate summary of the post-1990 rise and post-2020 decline of U.S. political polarization, illustrated below with the Vanderbilt Unity Index (VUI). The modern era of polarization by this measure began in the 1990s, though some other polarization measures show an earlier increase. The VUI combines measures of civic trust, political extremism, civic unrest, Presidential approval, and Congressional polarization. Lower values of the VUI indicate more polarization (less unity), and vice versa.

The mid-1990s ushered in the scorched-Earth partisanship in Congress pioneered by Newt Gingrich (elected House Speaker following the 1994 midterms), and the partisan cable news era (Fox News launched in 1996). Polarization briefly declined after the September 11 attacks, as the country rallied around its victims and the shared threat of terrorism. But the ensuing War on Terror—especially the war in Iraq—and expansions of the security state fueled more division. The globalization-fueled decline in U.S. manufacturing employment accelerated in the early 2000s, and sharply accelerated again during the Great Recession following the 2008 financial crisis. The recklessness of the big banks in causing the 2008 crisis, and the lack of accountability they received for it, stirred more public outrage.

Barack Obama’s inauguration in 2009—following a “hope and change” campaign ushered in a brief improvement in polarization. But a perfect storm of polarization ended up brewing during his term, fueled by: the slow economic recovery; the rise of viral social media, fueling outrage and early versions of cancel culture; tightening job markets in elite ‘chattering class’ professions such as journalism and academia (‘elite overproduction’), leaving these professions susceptible to extremism, posturing, and rent seeking; and inflection points in uneven progress on race and gender equality that ended up leaving people in all groups (non-white and white, female and male) feeling threatened. I may spend a future post explaining these trends in more detail. In the meantime, I recommend Musa al-Gharbi’s We Have Never Been Woke, Grossman and Hopkins’ Polarized by Degrees, Ezra Klein’s Why We’re Polarized, Lukianoff and Schlott’s The Canceling of the American Mind, Jonathan Haidt’s The Anxious Generation, and Lukianoff and Haidt’s The Coddling of the American Mind.

Donald Trump got elected in 2016, partly because of backlash to the early versions of what we now call ‘wokeness’—left-wing identity politics and cancel culture—and Hillary Clinton’s tepid but noticeable embrace of it during her campaign. It also didn’t help that Clinton was part of the early-2000s economic-policy and pro-Iraq-war establishments.

But Trump’s election supercharged wokeness, rather than stopping it (see figure below, from my earlier post). Trump’s election set both the woke left and moderates into a panic about his excesses and his associations with the far right. His election was easy for the woke left to sell to the public as evidence that America was an irredeemably sexist and racist country run by “mediocre” white men. Trump’s election also increased moderates’ fears of criticizing far-left excesses. Moderates did not want to inadvertently enable Trump, nor did they want to be lumped in with him in the eyes of their peers and colleagues. Trump’s election also energized the far right, of course.

All considered, Trump’s presidency emboldened extremism on both sides, and was rock bottom for polarization (see figure above). Remember: the extremes are each other’s best friends. One extreme is not the antidote to the other, as each would like the rest of us to believe.

I argued that market competition—for dollars, ideas, and votes—would unstoppably cause extremism, and consequently polarization, to recede. I argued that this would probably happen on the left first, because the far left represents a smaller constituency (~5-10% of the country, compared to ~15-25% on the right), and because the far-left’s bad ideas tend to produce more immediate and widespread harms that are easier for the average person to trace back to their bad ideas. Police and prosecutorial pullback causes crime to rise. Loosening border security increases illegal immigration rates. I argued that the nakedly bigoted and antisemitic responses to the October 7 attacks among a sizable fraction of far left—in some cases explicitly supporting Hamas or cheering on the violence—would permanently diminish the far-left’s claim to moral high ground.

Since I wrote this back in April, the decline of the identitarian far left has clearly continued, and perhaps accelerated. The New York Times explicitly made this argument in a Nov. 2 piece called “In Shift From 2020, Identity Politics Loses Its Grip on the Country”. They earlier published a long and damning piece about the University of Michigan (UM)’s diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programs, laying out how UM spent a quarter of a billion dollars and accomplished little besides alienating most people on campus (including the groups they were trying to help) and chilling the climates for teaching, research, and (especially damningly) cross-racial interactions. That’s quite a shift at the paper of record, which was pushing out writers like Bari Weiss and editors like James Bennett in 2020 for even tepid transgressions against wokeness. As the November 2 New York Times piece outlines, DEI is in retreat across corporate America, and to some extent in academia; Kamala Harris is running on patriotism, border security, and her record as a prosecutor; Harris is not foregrounding her identity as a reason to vote for her (which I think is smart); and progressive candidates are struggling to win primaries.

With Donald Trump in a dead heat with Harris for the presidency—and likely to be more emboldened and surrounded by sycophants this time than he was last time, if he wins—it is a bit harder to see the signs of weakness on the far right. But these signs nonetheless exist.

First, weakness on the far left translates into weakness on the far right (again, they’re best friends). All of the would-be symptoms of left-wing excess that Trump is running against are already decreasing on Biden’s watch. Crime, unemployment, and inflation are back down to pre-pandemic levels. It’s a minor economic miracle that inflation was brought down without causing a recession (though most voters probably don’t appreciate this). Illegal immigration has decreased sharply over the past year. Manufacturing employment is increasing (see above), and manufacturing investment has dramatically increased, in both the public and private sectors (see below). This investment means that even more manufacturing jobs are on the way. U.S. energy production, including oil and gas, increased during Biden’s term. The cultural power of the far left is decreasing, as described above. As I said in my previous post, the more the center and center-left tames the far-left’s excesses, the more the far right will be left fighting paper tigers and looking silly.

Second, the context of this election should be conducive to a Republican landslide, but they can’t seem to convert. There may be more Republican registrations than Democratic ones for the first time in decades. Republicans are preferred on voters’ top issues (immigration and the economy). Most Americans are unsatisfied by the direction the country is going in. The Democrats nominated a relatively unpopular nominee—the VP of their unpopular incumbent—whose performance on the campaign trail has been uneven. And yet, Trump still isn’t beating her. (And my prediction, for the record, is that Trump will lose tonight. Nov. 7 update: I got that wrong, for reasons I will discuss in a post later this week, but I stand by the rest of the piece, and on my bullish outlook for America.)

The 2022 midterms were similar. Inflation, crime, illegal immigration, and wokeness all actually were still at their high points, and yet the Republicans did not win a big red wave. The red wave failed to materialize largely because weak, Trump-endorsed candidates underperformed. In that election (unlike 2020 and 2016), the Democrats over-performed the polls. (I predict this will happen again today and Harris will win the election, but I don’t pretend to have high confidence, given how close the polls are. Nov. 7 update: Again, mea culpa.)

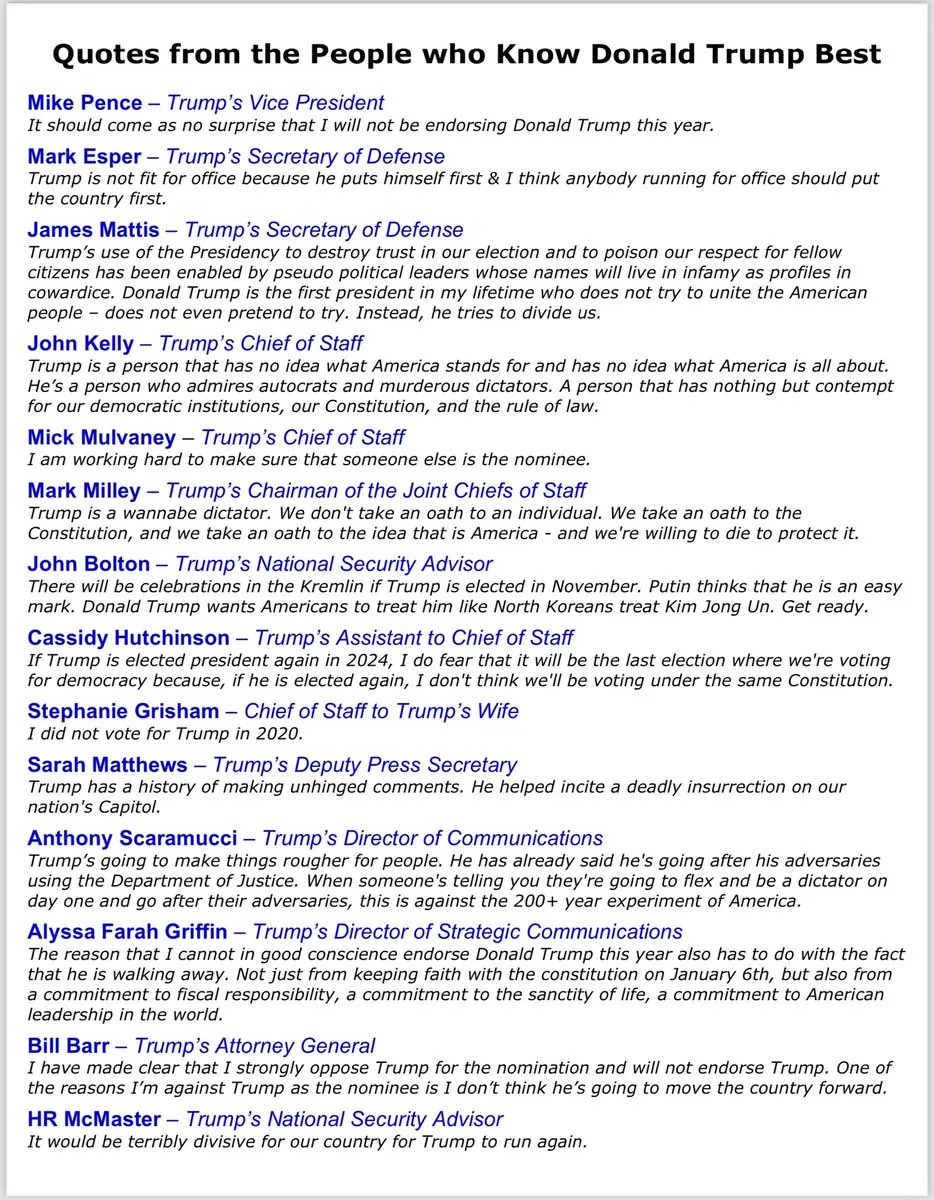

Third, while no challenger was able to beat Trump in the Republican primary, and most of his primary challengers have since endorsed him, many of his former staffers, generals, and political appointees have made damaging comments about him and refused to endorse his re-election. (See below, from Noah Smith.) This includes some people that previously have been called Trump sycophants (e.g., Mike Pence, Michael Cohen, Anthony Scaramucci). Trump’s current running mate, JD Vance, once called Trump a “moral disaster” and wondered if he was “America’s Hitler” (though he disavows these comments now). All this to say: it may be harder for Trump to build and maintain a new administration of sycophants than people think, even if he tries to.

Fourth, while Trump and some of his supporters seem to be laying the groundwork to challenge the results of this election if he loses, election officials in key states—including some Republicans—are taking steps to safeguard election integrity, seeing the post-2020-election chaos as both a stress test and a learning opportunity. Most (~95%) ballots are on paper, and some key swing states (e.g., Michigan) expect to have their results counted faster than they did in 2020.

Finally, even during Trump’s presidency, Republicans in Congress often moderated him. For example, John McCain stopped him from repealing the Affordable Care Act, and there is a broader appetite among the Congressional GOP to not revisit that again. Congressional Republicans did not allow Trump to gut climate-change-related science funding, which increased during his term, despite White House budget requests calling for sharp cuts. Politico reported recently that there may be enough support among Congressional Republicans for Biden’s major climate change laws to prevent Trump from repealing them. And there could also be some other areas—such as preventing an abortion ban or entitlement cuts—where Trump may moderate Congressional Republicans if he were to win a second term.

In essence, my argument is that polarization has been slowly but surely destroying itself on both sides over these past few years, and that this will continue no matter who wins.

How polarization will continue to destroy itself if Harris wins

Some people worry that the far left will be empowered under a Harris administration. After all, when she ran in 2020, she once endorsed the Green New Deal and fracking bans; she supported bail funds for post-George-Floyd rioters; she seemed to endorse equality-of-outcome ‘equity’; and she supported government-funded gender-transition surgeries for prisoners and illegal immigrants. Despite these past positions, I don’t think a Harris administration will preside over a resurgence of the far left, even if she wanted it to. It’s also not at all clear she would want a far-left resurgence.

The simple reason I expect the far left to keep losing power and polarization to continue declining, under a Harris administration, is that both of these things started happening under the Biden-Harris administration. There are good reasons to expect a Harris administration to govern similarly. Although she has not explicitly rebuked the extremes on her side—with a Sister Souljah moment—Harris’ campaign’s focus on patriotic messaging, its lack of emphasis on identity politics, and her pivots to the center on key issues such as immigration, crime, and energy policy suggest that she and her team understand that the far left is unpopular, whether or not she understands that many of their ideas are bad.

But the bigger reason to expect left-extremism and polarization to keep declining under a Harris administration is that the forces driving their decline both exist outside of the White House and show no signs of abating. Corporate America is retreating from divisive DEI policies because they’re bad for business and they’ve created legal and reputational exposure, not because of anything Biden and Harris are doing. The pendulum is swinging away (slowly, to be sure) from far-left ideological capture in universities for a number of reasons, that again have nothing to do with the Biden-Harris administration.

The eagerness of many far-left scolds to apologize for—and some cases embrace—Hamas and Hezbollah over the past year will render their scolding toothless in the future. The student protesters who allowed their movement to be literally infiltrated by genocidal foreign terrorist groups will be remembered by history as a sad punchline, not as a political force to be revered or emulated, like some student protesters of the past.

The point is: the far left is losing the battle of ideas, and sunlight is slowly but surely disinfecting their excesses of the past five-to-ten years. Institutions are reforming to protect their bottom lines, their enrollments, their good standing with donors and state governments, etc. Democratic politicians, including Harris, are gradually pivoting to the center to maintain support, too, whether they like it or not.

Even if a Harris administration wanted to try to stop the pendulum from swinging against the far left, she would be risking turning herself into a one-term President, wiped out by a red wave (assuming the GOP can nominate a normal person in 2028). My read is that she is more motivated by unprincipled ambition than she is by principled adherence to any of her more extreme positions from 2020.

What about fears that she’ll pack the Supreme Court? Biden didn’t pack the court, in part because surely he knows that a future GOP President could just do the same thing. So, court packing would be opening Pandora’s box. I doubt Harris—who is famously politically cautious—would go there either.

If I am right about the far left continuing to fade under a Harris presidency, then the far right will have trouble maintaining its momentum on her watch, too, for reasons I described above. Trump and his supporters will have a hard time selling the “far left is destroying our country” message if inflation and crime continue to fall, Harris signs a bipartisan border security bill (as she’s promised to do), and wokeness continues to recede.

Even if I’m wrong about all of this, it seems likely that a President Harris would face a divided government, with at least one branch controlled by the GOP. So, if she turns out to be unwilling to compromise (despite her promises to the contrary), she’ll be steering the country nowhere fast, not racing it off a cliff.

The other polarizing possibility, if Harris wins, is that Trump doesn’t concede and then he succeeds in causing a constitutional crisis, where he failed last time. It does seem likely that Trump will not concede and there will be some unrest before inauguration day if Harris wins. But with Biden (and Harris) in the White House, and any January-6/stop-the-steal effort lacking the element of surprise this time, I doubt we will see anything as bad as we saw in 2020 and 2021.

How polarization will continue to destroy itself if Trump wins

If Trump wins, I expect that polarization will temporarily get worse, like it did last time (see figures above). The rollercoaster of polarization in Trump’s second term would probably be worse than it was in the first term in some ways. For example, there would be fewer checks on his excesses from his inner circle, who would be more meticulously assembled from loyalists.

But his presidency would probably be less polarizing than last time in other ways. For example, he would probably not empower the far left as much as he did last time, due to the far-left’s weaknesses described above. He probably wouldn’t disempower the far left much either, though. He would certainly try, but any executive or legislative victory he won against the far left would be too easily tainted in the public eye by his divisive persona, which would make his victories susceptible to being rolled back by the next President or Congress. His “remain in Mexico” policy on immigration, and his Title IX reforms protecting due process on college campuses are two examples of policies from his last term that had moderate appeal and might have survived a new Democratic administration, had they not been passed by Trump and tainted by his brand.

Ultimately, I expect the country would survive a second Trump term, and polarization would eventually continue declining. Remember: it is popular opinion—and markets for votes, dollars, and ideas downstream of that—driving the current decline of polarization. So, to reverse the long-term decline of polarization, Trump’s presidency would have to either change public opinion (by persuading people or provoking backlash) or literally prevent these markets from working.

Although Trump has been very good at revealing issues where elite opinion was out of touch with popular opinion—for example, on trade with China and on illegal immigration—he has not been very good at persuading people to like him, nor at broadening his voter base. His support and approval ratings have been pretty-much flat for a decade. He has been neither interested in, nor skilled at, unifying voters outside his core base. Voters are tired of the constant division that has marked Trump’s time in politics.

Fears that Trump might try to abuse his power, if elected, to punish his enemies or undermine the Constitution seem well founded. He has at various times during the campaign promised to do each of these things. Such actions would, of course, undermine markets for votes, dollars, and ideas. But it seems much harder to imagine Trump succeeding on a scale that does lasting damage to the republic beyond his term.

For starters, Trump is 78 years old. The idea that he would serve four more years and then try to keep serving beyond that seems less plausible than it would if he were 20 years younger. Assuming Trump does fade from the political arena at the end of his term or shortly after, it does not seem likely that the next GOP presidential nominee would be able to easily co-opt Trump’s movement.

As others have pointed out, Trump’s movement bears more resemblance to a personality cult than an ideological movement. If Trumpism were an ideological movement, a more disciplined-but-aligned candidate like Ron DeSantis would have won the primary. It is difficult to replace a personality cult’s leader. Even if someone were able to consolidate similar support in the GOP base, it is not clear that they would have the same un-democratic instincts that Trump does. For example, while many GOP leaders avoid explicitly contradicting Trump’s lies about winning the 2020 election for careerist reasons, most (e.g., Ron DeSantis and JD Vance) seem unenthusiastic about these lies, and would rather avoid the subject.

As discussed above, Trump would probably face considerable—even if quiet—resistance from Congressional Republicans if he were to adopt an extreme legislative agenda. He would face even more resistance from a divided Congress.

Lastly, it would probably be harder than Trump might think to surround himself with people both so loyal as to never question any of his decisions, and competent enough to execute his agenda. Absolute loyalty on its own may be hard to come by for President Trump, as he repeatedly found out during his first term (see above). But loyalty and competence combined may be even harder, especially in areas like the military where specialized experience is critical. Trump does not have a record of earning the confidence or the loyalty of top military leaders. .

Foreign policy is one area where Trump presents a major wildcard, whose effects on U.S. polarization (and the world) are hard to predict. He has been described by his opponents as feckless, easily manipulated, and too admiring of hostile foreign dictators like Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping. These traits could embolden America’s enemies if Trump wins, for example, to escalate military campaigns in Ukraine and Taiwan, or to escalate spying, cyberattacks, and terrorism against the U.S. On the other hand, Trump’s supporters argue that his bravado and erratic nature act as a deterrent to hostile foreign countries who see him as unpredictable and prone to lashing out on a whim. Both of these descriptions of Trump seem accurate to me.

All considered, a second Trump term would probably be a bumpy ride, with real downside risks, but the republic would survive. America has an unusually strong system of checks and balances. Most of the public is tired of the drama and division.

We should not be complacent about polarization

My prediction that America will win its battle against polarization and extremism is not a call for complacency. To the extent that we have made progress against extremism on both sides since 2020-2021, it has been hard-won progress. People and organizations from across the political spectrum have been working to expose bad ideas, to persuade people of better ones, and to organize new political movements. Some people are organizing against polarization itself. Civil servants are working diligently and honorably to protect the integrity of today’s election and future ones.

I don’t think it’s my place to tell you whom to vote for, but I hope you will vote (if you’re eligible). This election offers a stark choice between two very different candidates. Their ideas are different. Their approaches are different. Their effects on polarization are likely to be different, at least in the short term. There is no realistic third-party option. Choose wisely. Whoever wins, let’s all continue the grass-roots work of building bridges and un-dividing our great country from the ground up.

I just reread your ‘what if Trump wins’ scenario and hope that it comes to pass with a lean towards the benign. I anticipate a bunch of American Orbán-type operatives to try to take advantage of the situation to rejig the game for future elections (by influencing the media, courts and electoral mechanisms. It will be interesting to see how vigorous the democratic immune system responds.

What weight do you give to the idea that voters in the primaries tend to be more extreme which is why we end up with candidates that embrace more extreme positions? Harris is unique in this regard because she was able to avoid the primaries.